When Leslie Auceda was in the sixth grade, her mother arrived at George Washington Middle School for a parent-teacher conference ready to learn about the progress her daughter was making in school. But she did not speak English, so she waited; after an hour and a half of waiting, Leslie’s mother surmised that the teachers were giving preference to the English-speaking parents. So she gave up and walked out — never to return to another parent-teacher conference.

As Leslie moved toward graduation, she said, she had a growing suspicion that she was receiving different treatment than her white classmates.

"When we would sign up for classes every year, I noticed the counselors would recommend that the white students take honors classes but the Hispanic students and black students were told to take regular classes," said Auceda, who graduated from T.C. Williams High School earlier this year and now attends Northern Virginia Community College. "The counselors would say that the classes were too hard for me, and that I wasn’t up to the challenge."

Auceda’s story is one of the many voices contained in a controversial report issued last month charging that Alexandria City Public Schools has a "two-track system" — one in which a privileged white minority receives an education that sets them on a path for college while black and Latino students are marginalized or ignored. The report, titled "Obstacles to Opportunity," was issued by George Mason University Sociology professor Tony Roshan Samara, the Advancement Project and Tenants and Workers United. Much of the commentary in the report was based on a survey of Alexandria public-school students — some of which were conducted on city-issued laptop computers during class time.

But administration officials bristled at the conclusions in the study, charging that the report’s authors did not consult them during their analysis and released a final draft to the public before offering them an advance copy.

Director of Secondary Programs Margaret May Walsh penned an official response shortly after the report’s release, issuing a point-by-point refutation of the study’s findings and alleging that the authors used selective citations of a student survey to make sweeping conclusions. Much of her criticism was aimed at the survey, which she said had "validity issues" because of the way questions were formatted and ordered.

"To use the results of this survey as the basis for the commentary in the report is highly suspect and would not pass the lowest benchmarks for university research," Walsh wrote. "The decision to use this survey should be problematic to the authors and to their sponsors."

<b>THE DEBATE OVER</b> race and education has its roots in the old system of segregation that once separated whites and blacks into different schools — a phenomenon that the Supreme Court found unconstitutional in the 1954 landmark decision in Brown v. Board. In Virginia, leaders such as Sen. Harry Byrd led a "massive resistance" effort to oppose desegregation. But Alexandria’s schools were eventually integrated in the 1960s, and in 1971 T.C. Williams High School centralized all of the city’s public-school population into one building — a racial mixing pot famously portrayed in the Disney movie "Remember the Titans."

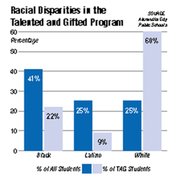

But the real-life story did not have a Disney ending. Racial gaps continue to plague the school system, and "Obstacles to Opportunity" documents some of lingering disparities in test scores, discipline practices and counseling directives. Using standardized test score data from the Virginia Department of Education, the report’s authors show that white students in Alexandria outperform other students statewide while black and Latino students consistently scored lower than their counterparts in other parts of the commonwealth. One prominent criticism the report levels at the school system is the heavily white makeup of the Talented and Gifted program, which teaches higher level thinking processes at an accelerated pace in an environment conducive to risk-taking and exploration of new ideas.

"The low rates of college preparation for black and Latino students can be traced in part to how ACPS structures its academic program and the emphasis placed on the Talented and Gifted Program," the report concludes. "The TAG program in ACPS is exclusive and also racially unrepresentative of the overall student population, with black and Latino students again being dramatically underrepresented. Yet the ACPS curriculum is structured is structured so that the chances of a child receiving a college preparatory education are dictated by whether he or she is selected for the TAG program by the time they reach sixth grade."

Students can be identified for the TAG program in a number of ways, typically through a referral by a teacher who has made classroom observations. But parents can also submit a nomination form to initiative the process. Ultimately, an Identification Placement Committee makes the final decision based on standardized achievement test results, grade averages, learning characteristics checklists, information from parents and creative product ratings. Between Kindergarten and third grade, TAG-identified students remain in their regular classrooms and receive a differentiated instructional program in language arts, math or science. By the time students are in the fourth-grade, the TAG-identified students leave the regular classroom and receive daily instruction in language arts and/or mathematics in a specialized section with a designated teacher.

"There’s a perception in this report that being in TAG puts you on a track for college, but that’s not the case" said School Board member Eileen Cassidy Rivera, who serves as the board’s liaison to the Talented and Gifted Advisory Committee. "One of our biggest problems with TAG is that we don’t communicate enough with parents about how to get their kids involved. Most parents don’t know that they can nominate their own child for the program because they think that a teacher has to do it."

<b>PROPOSALS FOR REFORM</b> have become hot topics of conversation since the program’s release. Some say that the school division should be forced to have a TAG population that models the racial demographics of the division. Others say that separating the students is inherently equal and that the TAG program should be dismantled in favor of classrooms with wide varieties of learning abilities. Yet despite the debate over the specifics of reform, many school administrators say that they agree with the broad outline of challenges identified by the report.

"Our goal is that all students are prepared for college and the world of work," said Amy Carlini, executive director of Information and Outreach for the division. "We do not have a two-track school system, but we could certainly do a better job of letting students know about the opportunities that are available to them."

One proposal identified in the report that is building a growing number of supporters involves changing the way students are disciplined. Citing statistics indicating that Alexandria suspension rates are twice as high as the national average, the report called discipline practices in the city schools as "creating an unsupportive school environment that leads to students dropping out of being pushed out." To change this phenomenon, the report suggests, school officials could adopt a strategy of "restorative justice" — a theory of criminal justice that focuses on crime as an act against another individual or community rather than the state. Tony Roshan Samara, the George Mason Sociology professor who helped write the report, said that the school system could keep more at-risk students in the classroom by adopting restorative-justice techniques similar to the ones used by the South Africa Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

"When they are given a chance to speak their mind, even bullies start to feel an obligation to the culture of the school," said Samara. "But the traditional model of forcing students to miss classes as a form of punishment causes them to be even less invested in their own education than they were before."

<b>PERHAPS THE MOST</b> controversial finding in the report is the charge that T.C. Williams has a "minimalist college-going culture" in which counselors and teachers do not act as aggressive advocates for motivating students to consider college. The survey performed last year showed that 45 percent of students said their counselor had not helped them plan the courses they needed to get into college. That sentiment was strongest among the Latino students, 51 percent of whom said they had not received such assistance.

"I don’t believe the survey," said T.C. Williams Principal Mel Riddile. "And it’s patently untrue that T.C. Williams has a minimalist college-going culture. I don’t know how anyone could draw that conclusion."

Riddile said that he has never worked in another school division that does more to prepare all of its students for the future than Alexandria, and he has implemented a literacy program that has been designed specifically to prepare children for the challenges of living and working in the 21st century. He said that the past six years, the school division has increased participation in honors or AP classes by 39 percent. Furthermore, he said, groups such as the Alexandria Scholarship Fund raise money to help low-income families afford college. Although he said he agrees in principle with the goal of increasing the number of students who are on a path to college, he said that most of the recommendations listed in the report are already being implemented.

"I’ve done this before in other schools, and we’re going to do it again," said Riddile. "But it’s not going to happen in a day."