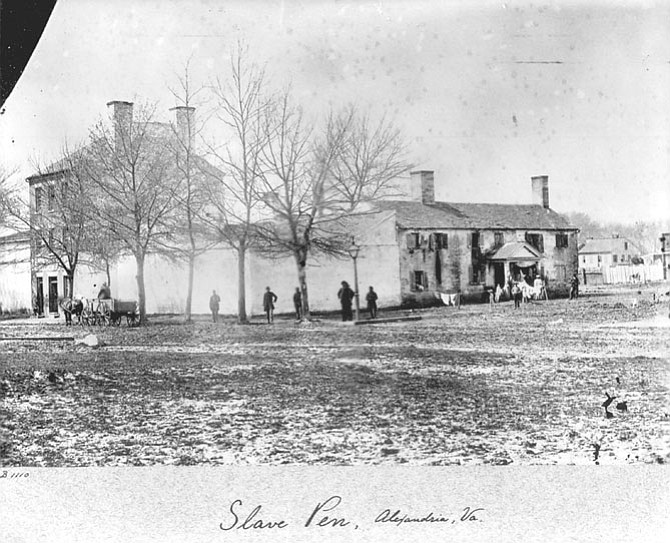

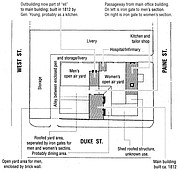

Civil War-era photo of Franklin and Armfield Slave Pen. Showing the original 1812 main building (on left, three-stories with the two chimneys), the probable kitchen and tailor shop (low building on right with two chimneys), and some sort of roofed area of unknown use behind the white-washed wall. Library of Congress

Alexandria — Franklin and Armfield’s slave-trading “establishment” was located near the outskirts of what was then, in the 1830s, the town of Alexandria. The main building was three stories, handsomely painted, with green blinds. Appended to the main building was a large yard, perhaps 300-feet square, enclosed by a high "close board fence" neatly whitewashed and filled with numerous small buildings. Over the door hung a simple sign: "Franklin and Armfield." Inside the fence was a high brick wall, also whitewashed, with the enclosed courtyard about half covered by a roof.

The pavement inside the wall was reported to be clean, with a pump in the center to provide an "ample supply of water." In the roofed area was a large table where the slaves ate from tin plates, The fare was bread and boiled meat which the abolitionist visitors found wholesome in quality and sufficient in quantity. The courtyard was apparently used only for exercise and meals. Otherwise, the men and women were sequestered separately in cellars, the children staying with the women.

The abolitionist visitors also found that the slave men were well clothed with shoes and stockings, which was apparently the Virginia standard. The only raggedly clothed boy was from Maryland. "That's the way they come from Maryland," Armfield said, "you see the difference.” The women and girls were also clothed in "coarse but apparently comfortable garments.”

In the cellar, both the rooms, which separated the slaves by sex, were provided with fireplaces or stoves for warmth. Next to the yard was a kitchen where the slaves' food was prepared, and a tailor's shop where the slaves’ clothing was made. Before embarking for New Orleans, each slave was provided with two entire sets of clothing from the shop. The visiting Boston abolitionist Andrews found the clothing well made of good materials, with the women's wardrobe showing "considerable taste."

In the corner of the yard was a hospital, which in January 1834 contained a sick, old woman, whom Armfield had refused to buy, and a young woman with an infant beside her on a pillow, indicating a recent childbirth. In July 1835 the hospital was empty. Each of the slaves was provided with a blanket which was hung in the sun during the day. Both men also commented on the many iron bars, door grates, and security bolts to be seen everywhere. This was a clear reminder that the blacks were not there by choice, and that the facility was, in fact, a prison.

Most of the slaves appeared to these visitors to be contented. The Rev. Joshua Leavitt could not discover "any indication of despondency or unhappiness;" Andrews reported the slaves "were standing about in groups, some amusing themselves with rude sports, and others engaged in conversation, which was often interrupted by loud laughter.” Several of the women were clutching young children tightly to themselves, as if to prevent any separation.

Leavitt was able to visit the Tribune, which was loading at that time in the Alexandria harbor. He was told by Armfield that the firm had purchased its own ships to prevent overcrowding, which resulted in the slaves becoming sick and arriving at the market "in bad order." But Armfield was no humanitarian. It was to his financial interest to have the slaves appear fresh and healthy, and John Armfield was a man who protected his interest carefully.

The hold of the Tribune was divided into two compartments, one to transport about 80 women and the other about 100 men. "On either side were two platforms, running the whole length, one raised a few inches, and the other about half way up to the deck." On the platforms, which were about 5 1/2 to 6 feet deep, the slaves would lie as closely together as possible.

The captain of the Tribune observed that the slaves were not forcibly confined, that he did not even lock his hatchway, but allowed the slaves to come on deck as they pleased, and that he never had the least difficulty with them. Leavitt, a minister, commented that the enslavers should also not "lock down the hatchways upon the mind of the slave, and keep him from a free enjoyment of the light of heavenly truth."

The visit to Alexandria altered Leavitt's view of the trade. While adamantly opposed to slavery in all forms, he refused to condemn Armfield. "The very men who sell him slaves in Alexandria, and those who buy them in New Orleans are respectable," he wrote. "Judge (Bushrod) Washington sold his slaves from Mount Vernon; ... I have met here a minister of the gospel who told me without remorse that he had bought a slave and afterwards sold her. A member of one of our Presbyterian churches," he continued, "sold another member of the same church, to go to New Orleans." Thus, Armfield as a facilitator of the trade should not, in Leavitt's view, be singled out for social censorship. However, whatever Leavitt's opinion was of this respectable trader of human beings, closer analysis of John Armfield's business indicates he was shrewd rather than kind, and that he had his personal profit, not the slaves’ well being, uppermost in his mind.

When Franklin and Armfield's ships arrived in New Orleans, they were required to turn in to the Collector of Customs a manifest, which had been certified by the Customs Collector at Alexandria, listing each slave by name, age, sex, height, and color. The purpose of this manifest, with a detailed description of each slave onboard, was to assure that none of the slaves on the ship were from outside the United States, such as being exchanged for African slaves at sea. A close analysis of more than 3,500 slaves listed on the manifests for 28 shipments from 1828 to 1836 provides a unique insight into just what the trade meant to the African-American slave community from which Armfield drew his supply.

Most of the slaves were young men and women apparently without families. Over 80 percent of the women with children were without apparent husbands, and most of the women appeared to be without husbands or children. Apparently Armfield was willing to purchase women with children, but had few qualms about separating male slaves from wives and family.

Three-quarters of the males and 90 percent of the females were under the age of 25. Nearly half the women were under age 16. This is not surprising, as young single slaves, the so-called "prime field hands," would be easiest to sell and would bring the best prices at New Orleans. How then did Armfield assemble such a large proportion of young, single slaves, especially women?

Andrews had been told that women with children were harder to sell than those without. Analysis of the slaves that Armfield shipped from Alexandria strongly suggests that he regularly separated young women from their children and husbands. The high percentage of single males supports this view that Armfield did separate both men and women from their families in order to procure the young, single individuals who would bring the best price on the New Orleans market. Indeed, an unnamed slave trader whom Andrews met on a Potomac River steamer attested that he often separated African-American slave families. The trader added: "I have often known them to take away the infant from its mother's breast and keep it, while they sold her." Although the trader was speaking of his, not Armfield's, experience, Armfield purchased from the same market, and clearly operated in a similar manner.

Four-part Series

See the entire four-part series as it appeared in the Alexandria Gazette Packet by clicking the link below:

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade

Or read each part online by clicking the links below:

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part I

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part II

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part III

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part IV

More like this story

- Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part IV

- Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part III

- Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part I

- City of Alexandria to Purchase Freedom House to Preserve Historic Museum

- 400 Years of Slavery