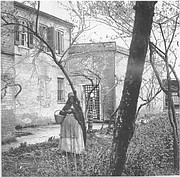

Photograph of the former Franklin and Armfield “Slave Pen,” during the Civil War. The building had been sold to Price, Birch & Co. in 1850. From the National Archives

The extent of the forced separation and sale of young slave children away from their mothers has long been a vexing question, and historians have often been especially concerned with this issue. In 1931, the historian Frederick Bancroft asserted that "the selling singly of young [black slave] children privately and publicly was frequent and notorious." He added that such children were "hardly less than a staple in the [interstate slave] trade."

In 1975, two American scholars (Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman), utilizing computer analysis, declared that this was not so, that the percentage of black slave children under age 13 sold at New Orleans was only 9.3 percent, and amounted to no more than 234 per year. The historian Herbert Gutman attacked these results in the New York Times, claiming that the computer had "trivialized the number of children sold." A careful analysis of the shipments by John Armfield in Alexandria to Isaac Franklin in New Orleans, however, provides a different and more useful understanding of the number of young slave children sold separately in the Alexandria to New Orleans trade.

Statistical analysis of the 3,570 slaves on the Alexandria manifests shows that 145, or 4.5 percent, were under age 10, and 308, or 8.62 percent, were under age 13. Thus, it would appear that the percentage of children in the Alexandria shipments supports the computer analysis. On closer examination, it is not so simple.

In January 1829, the Governor of Louisiana signed into law new legislation prohibiting the separate sale of children under 10 years of age, or of mothers from children of similar age, except orphans. This meant, of course, that single children under age 10 purchased in Virginia or Maryland by John Armfield could not be sold in New Orleans by Isaac Franklin. Indeed, the apparent necessity for such statutory prohibition of the separation and sale of young slave children in Louisiana, clearly indicates that such sales were frequent and common. Further, this new statute greatly affected the way in which Armfield bought slaves.

Among the slaves in the shipments from Alexandria to New Orleans before the new law took effect, single children under age 10 comprised about 13 percent, and under age 13 over 20 percent. This is over twice the 9 percent predicted by the computer analysis of Fogel and Engerman. For the first three shipments after the new law went into effect, the percentage of single children under age 10 shipped by Armfield dropped from 13 percent to zero, and of children under 13 from 20 percent to 3 percent.

Clearly, the new Louisiana legislation had a significant effect on which slaves were purchased by John Armfield.

That this was not mere coincidence is apparent by two other factors. Prior to February 1829, Armfield advertised in the local papers for slaves from 8 to 25 years old.. The next advertisement in April 1829, when the sale of children under 10 was prohibited in New Orleans, offered to buy "likely Negroes from 12 to 25 years of age, prime field hands." The offer to buy young children, who he could not sell, had been withdrawn. Additionally, there was an enormous increase in the number of children listed on the manifests ages 11 and 12 over the number ages 9 and 10 in Armfield's shipments after April 1829. He was again buying in accordance with the law, in order to maximize his profit. Armfield exhibited little concern about keeping slave children with their mothers, when he purchased so many single children ages 11 and 12. And, the true cost of such transactions was paid by the African-American children he bought and by the mothers from whom the children were separated.

Finally, the trader that Andrews spoke with on the Potomac steamer admitted that he sold many young children separately in Carolina (where there was no law prohibiting their sale), but added: "they won't go in Mississippi; Armfield never takes them if he can help it." This was in 1835; back in 1828 when he could still sell young, slave children, Armfield obviously "took them," as 20-percent of his slave shipments were such children. When he changed his advertisements to buy slaves and when he bought no children under age 10 after the new Louisiana law, John Armfield was simply responding to market reality, and was not acting out of any concern for African-American slave children. Armfield, a businessman, simply bought what he could sell.

It was also no coincidence that in 1833, 1834, and 1835, the very time Armfield was visited by abolitionists who had come to Washington to press antislavery with the Congress, that Armfield increased his purchases of slaves in family groups. Abolitionism was very strong in the early 1830s, and the breaking of slave families by the slave trade received special condemnation by the abolitionists.

It was thus for good reason that Armfield's assistant assured the visiting abolitionist Andrews, in 1835, that “they were at great pains to prevent" the separation of families and “to obtain, if possible, whole families. .. In one instance,” the clerk continued “they had purchased, from one estate, more than 50, in order to prevent the separation of family connections; and in selling them, they had been equally scrupulous to have them continue together." This had cost the firm "not less than one or two thousand dollars, which they might have obtained by separating them," as they sold better in small lots. It was, the Reverend Leavitt thought, ultimately profitable for the firm to lose on an isolated sale" in order to gain the good will of farmers and planters in Maryland and Virginia."

Armfield told Leavitt that "he would never sell his slaves so as to separate husband and wife, or mother and child." The trader said he had been offered a troublesome slave "for twelve and one half cents, if he would carry him to New Orleans." Armfield asserted that he had refused to purchase this slave, even at such an attractive price, as "the fellow had a wife in the neighborhood and they did not like to be separated." It is unlikely that Armfield actually bought with such care. And, a cursory analysis of the slave sale records in New Orleans indicates that Franklin regularly divided slave families for easier sale. But, it was shrewd business for Armfield to have good public relations with the local Maryland and Virginia slave owners.

Whatever Armfield said or Leavitt heard, it is obvious from the high percentage of young, single, African-American slave men and women that Armfield shipped from Alexandria to New Orleans, that the sale and transportation of local Virginia and Maryland slaves resulted in many broken families and many separations from family and kin. For the African-American slaves involved, the price of Armfield's profit was very high indeed. This was especially so before it became good business to buy slaves in families. Even so, at all times, the ready market for prime-age, single men and women in the Deep South and the high percentage of such individuals among the Alexandria shipments testify to the disastrous effect of the marketplace on African-American slave families.

Continued in next week’s Gazette Packet.

Four-part Series

See the entire four-part series as it appeared in the Alexandria Gazette Packet by clicking the link below:

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade

Or read each part online by clicking the links below:

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part I

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part II

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part III

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part IV

More like this story

- Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part IV

- Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part II

- Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part I

- City of Alexandria to Purchase Freedom House to Preserve Historic Museum

- There’s No Place Like Home in Alexandria