In its draft FY19-28 Capital Improvement Plan (CIP), the School Board has pared back its 10-year funding request to City Council from last year by nearly a quarter — from $611 million to $475 million. This results from the School Board’s incorporating an advisory task force’s recommendations to delay and remove certain projects in order to align with identified available funding from the city coffers. However, despite the task force’s streamlining, the school system still faces a growing deficit of seats in light of increasing student enrollment.

The School Board postponed adopting its FY19-28 Capital Improvement Program (CIP), pending further discussion about how to articulate its total capacity needs while simultaneously acknowledging budgetary constraints.

“The budget tells a story,” said School Board chair Ramee Gentry. However, that the School Board depends on City Council for revenue poses something of a conundrum about how to tell that story: “Do we want this budget to articulate a need, or a reality of what we can do about that need?” asked School Board member Veronica Nolan at a Dec. 19 work session.

Or, as School Board member Bill Campbell put it in a later email: “Is a school board tasked to ask for what it needs or should it also consider all of the other constraints as identified by council and constituents?”

To clarify their story, the School Board voted Jan. 11 to delay CIP adoption until Jan. 25. They’ll discuss at an additional work session Jan. 18, not further adjustments to dollar figures, but how to hone qualifying language in their CIP document and adoption resolution. School Board member Karen Graf said: “Certainly this is a huge year for our community. There is nearly a half a billion dollars being distributed across a 10-year period to pay for builds and improvements around the city — not only for schools but for city properties as well.” She supported the delay in order “to really get the language around how we want to communicate to city council … what our philosophy is around this particular CIP.”

Over time, School Boards have not consistently weighed the tension between needs and constraints. In the past two years, their CIP requests have varied dramatically.

Describing the FY18 budget context, School Board member Christopher Lewis said last March that City Council had asked the School Board “to come forward with, what would it take to close the seating gap?” The seating gap — student enrollment growing faster than the addition of space — is the schools’ most pressing budgetary challenge. Answering council’s request, the School Board’s CIP request more than doubled, from $291 million in FY17 to $611 million in FY18. In his budget proposal Feb. 21, City Manager Mark Jinks said: “We can’t afford the whole thing — $611 million is simply too big a number.” In a March 9 letter to the editors of local newspapers, he said: “While these are important projects, it would be unprecedented for the city to suddenly provide such a large increase in funding to take on such an ambitious capital effort,” especially “within just 10 years.”

Now going into the FY19 budget season, the School Board has pared back its request by nearly a quarter compared to last year, to $475 million. This results primarily from their incorporating recent advice from the Ad Hoc Joint City-Schools Facility Investment Task Force. The task force recommended how best to prioritize 28 city and schools facility projects over the next 9 years. In order to fit everything into identified available funding streams, they delayed or removed several slated projects from that timeframe — including, for example, an expressly designated new middle school and a new pre-K center. This helped close an initial funding gap of $46 million to $4 million. The School Board has mostly adhered to the task force’s recommendations, “with only slight adjustments for cost estimates and for non-capacity items,” said Helen Lloyd, a schools spokesperson, in a Dec. 5 statement. And in their subsequent add/delete process, they ultimately included only $16 million of a net $222 million in proposed project additions and accelerations. Of that, $9 million for designing a new elementary school after FY28 comprises the only new project beyond what the task force recommended.

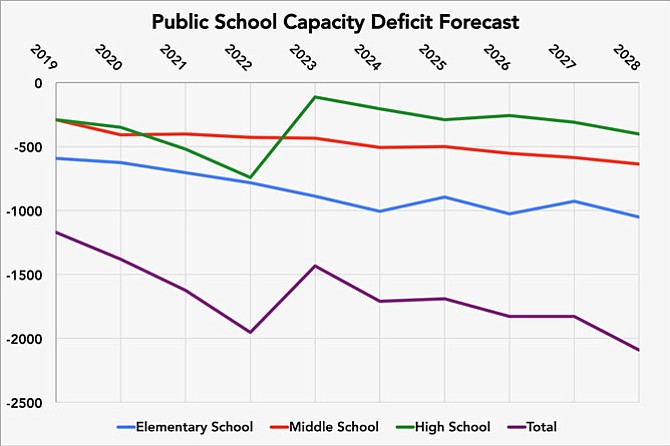

But a consequence of this paring back to align with funding availability, which the task force acknowledged, is that certain recognized needs remain unmet. In its draft CIP, the school system estimates that its seating deficit will still increase from about 1,200 in 2019 to about 2,100 in 2028.

“I think there are going to be some folks in the community that think that because the task force came in and we’re all ‘Kumbaya’ now with city council that this 10-year plan here is, if it’s not fixed all of the problems, it’s fixed most or a lot of the problems,” said Campbell on Dec. 19.

He thinks the task force’s recommendations are insufficient. During the add/delete process, his proposed project additions and accelerations comprised over half the School Board’s total. “Maybe we need to show another five years [of capacity projects beyond FY28.] … I just want to make sure we’re giving the entire picture.”

“The students don't go away just because our budget documents don’t show an ability to accommodate!” he added in a later email. “We need to show how we plan to address the seats issue, even if we can’t get to the ideal scenario (3 additional schools [one each of elementary, middle and high]). So I’m not saying that the school board should demand all of the money that we ‘need’ but rather we all need to collectively agree as to the total need, and then agree that as we move forward, both [council and the School Board] have plans to ‘make due.’ Right now, we are not showing how we will make due.”

Lewis expressed discomfiture with what he called vagueness in the draft CIP, particularly with regard to a needed new middle school. Following the task force’s advice, the School Board allocates funds to build a new campus, first to accommodate students during construction and upgrades. After the completion of all new construction, sometime beyond the present FY19-28 timeframe, this so-called “swing space” would convert to a permanent use — potentially a new middle school, though that’s not yet specified. The draft CIP also includes funds for land acquisition toward building a new school, though what kind is also currently undecided.

“It gets to, really, the philosophy of the board on if we want to show all the need in the 10 years so that it’s all on the table for a [future joint facilities] master plan. It would be good to specify” intended uses, said Lewis on Dec. 19.

What others dubbed vagueness, Gentry says she would prefer to call flexibility.

“There’s going to be some parts of this [e.g., land acquisition funds] that, no matter what we do in this process, we will not be able to put a definitive year or a definitive name on the item at the time that we pass this CIP.” There are still too many unknowns, such as the size of land acquired and potential grade reconfigurations (K-5 vs. K-6 elementary schools). “But I think by this time next year we’ll be much farther along,” she said.

Still, the draft adoption memo says that, in this CIP request, “a significant capacity and building condition need will remain unaddressed” and that “interim measures to meet the growing enrollment” will remain necessary.