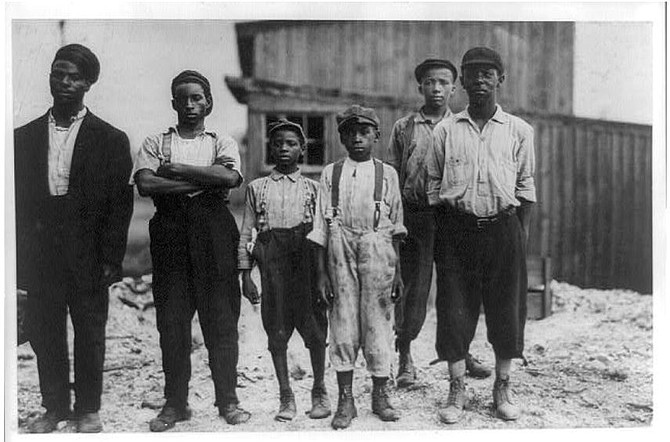

“The Negro Work Force of the Alexandria Glass Factory.” The picture was taken in 1911. National Child Labor Committee collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In late 19th and early 20th centuries, Alexandria attracted a number of factories and businesses. Prior to 1920, four glass factories settled in Alexandria. These glass factories were Belle Pre Bottle, Virginia Glass, Alexandria Glass, and Old Dominion Glass.

Many children and adults worked for the glass factories including African Americans (Negroes) who worked beside white Americans during this era of segregation. During this time, these factories used cheap labor for low skilled positions. The cheap labor consisted of poor and unskilled individuals, women and children. The glass factories were notorious for using child labor. Unfortunately without these children working at the glass factories, many of their families would not be able to meet their basic needs.

Some of the African Americans who worked at these glass factories were: a 13-year-old Charles Taylor, a laborer lived on Franklin Street; 52-year-old Abraham Brown, a carpenter, who lived on First Street; 17-year-old Abraham Lomax, Jr., a laborer, lived at First Street; 42-year-old, Emma Thomas and her 22-year-old daughter, Virginia Knapper who worked as carriers and lived on First Street; 15-year-old Lawrence Dawkins, a laborer who lived on Oronoco Street; 16-year-old Lloyd Montgomery Arnold, a laborer, who lived on Duke Street; 14-year-old Henry Anderson, a laborer, who lived on North Henry Street; 28-year-old Charley Spotswood a laborer, who lived on Bashford Lane; and 24-year-old Chauncey Randolph, a wagon driver, who lived on Columbus Street. These employees worked on rotation shifts, alternating their work schedules from day to evening shift. Many of these employees were able to contribute to their families’ income and some of them were able to purchase their homes like Abraham Brown and Charley Spotswood.

The glass factories had many problems. Those factories experienced a number of fires at the plants, equipment failures, fines against the factories for disobeying the child labor laws and the prohibition of alcoholic drinks that impacted their customers. A good amount of the glass factory revenue came from selling glass bottles to beer companies. Due to the prohibition laws on alcohol, many of the beer breweries closed. On top of those problems, the Great Depression sealed the fate of the glass factories. Many of the African Americans who worked for those factories found employment at the Navy Yard, Potomac Yard, Railroad, Wood Yard, Shipping Yard and the Torpedo Factory.

When World War II began, a great number of people were needed to help in the war efforts. The African Americans who worked at the glass factories had useful skills needed during the war.

Today many of the African Americans’ descendants of the glass factories are still living in the Alexandria, District of Columbia and Maryland areas. Some of these families have glass heirlooms from the glass factory like Emma Taylor and Virginia Knapper. Virginia’s daughter, Dorothy Knapper-Taylor, held on to the little glass pig that her mother and grandmother had from the glass factory. Mrs. Taylor died in 2013 at the age of 99. The little glass pig has been in the family for over 100 years.

Historically, Alexandria’s African Americans have contributed to the workforce that built Alexandria’s strong economy to this day. They are proud of their family legacy of hard work and that contributed to the Alexandria’s thriving economy then and now. As the descendants of the glass factory, they stand tall and proud to have been a part of the 20th century Industrial Age.

Char McCargo Bah is a freelance writer, independent historian, genealogist and a Living Legend of Alexandria. See her blog at http://www.theotheralexandria.com for more about “The Other Alexandria.”

More like this story

- The Other Alexandria: The Military Made My Life Better: Sergeant Donald L. Taylor

- Revisiting Family History

- The Other Alexandria: Working at the U.S. Navy Torpedo Plant

- History: The Other Alexandria: Alexandria World War I African American Veterans

- The Other Alexandria: Eugene Shanklin: Buffalo Soldier, WW I Veteran