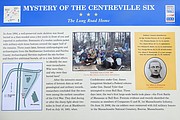

Unveiling of a historical marker honoring the Civil War soldiers found in Centreville. Former Sully District Supervisor Michael Frey is in red shirt; James Lewis is standing to the right of the marker. Photo by Bonnie Hobbs.

Most people just think of the Centreville McDonald’s on Fort Drive as a place for burgers and fries. But those lucky enough to be here in January 1997 also know it as the site of one of the most extraordinary events in Centreville’s history – the exhuming of the remains of six Civil War soldiers.

“It was one of the most amazing days in my career of 24 years on the Board of Supervisors,” said former Sully District Supervisor Michael Frey. “It was so exciting and so much fun.”

He was addressing the 80 or so people who came to that McDonald’s parking lot, Saturday morning, May 18, 2019 for a special ceremony commemorating that time and the unveiling of a historic marker. Attendees included local residents, history buffs, relic hunters and the event’s organizer – the Bull Run Civil War Round Table (BRCWRT) – which meets monthly at the Centreville Regional Library.

Frey recounted several, important events in Centreville’s history – including George Washington staying here as a young surveyor, the devastation caused by the Civil War, and Lee Highway becoming the first paved road in Fairfax County. “Centreville is an example of the evolution of an American community,” he said. “And people appreciate that we’ve preserved its history.”

Kevin Ambrose, of the Northern Virginia Relic Hunters Assn. (NVRHA), found the first grave in 1994, but no one investigated further until the rest were discovered, 2-1/2 years later, just prior to construction of the McDonald’s. It had to move to its current site because its old restaurant was demolished for construction of the Routes 28/29 Interchange.

LOCAL HISTORIAN and NVRHA member Dalton Rector – who was later instrumental in helping determine the soldiers’ identities – said they “were found in what’s now the drive-through lane for fast-food pickup.”

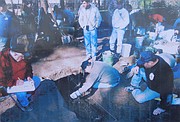

The astonishing discovery led to a three-day archaeological excavation, beginning Jan. 30, 1997, under the direction of world-renowned, forensic anthropologist Doug Owsley of the Smithsonian Institution. Skeletons and historic artifacts from the gravesites were measured, cataloged and removed.

“So many people came to see the dig,” said Frey. “Union Mill Elementary Principal Brenda Spratt brought classes here to watch, and people parked on both sides of Route 28 and crossed the road to see. I actually got to go into one of the graves and work with Dr. Owsley. That soldier was exposed from the waist up, but there were buttons and bits of clothing. One soldier had his boots intact and some wore the coats of Union soldiers. Spending three hours next to Dr. Owsley is something I will never forget. And I thank you for coming out today to show your passion for history and love of community.”

The soldiers were from Companies G and H of the 1st Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment, which sustained heavy casualties during the Battle of Blackburn’s Ford. They died on or shortly after July 18, 1861, three days before the Battle of First Manassas – considered the first battle of the Civil War.

“The heat was oppressive, and water was scarce; the soldiers drank from puddles in the road,” said the BRCWRT’s James Lewis. “The Massachusetts unit was in a five-hour battle with the Confederate soldiers. The next day, Union forces retrieved their dead and buried some of them in the area, likely marking their graves with wooden crosses.”

The war raged on and, that fall, said Lewis, 40,000 Confederates “encamped in Centreville for the winter. They cut down all the trees and burned every stick they could find – including the markers on the makeshift graves – for warmth.”

Fast forward to May 7, 1994, and Ambrose was relic-hunting at that site, popular with his group because of its history. “My metal detector picked up a faint, iron reading – which was coffin nails,” he told the crowd on Saturday. “I dug about 18 inches down and found little bones – toes – and two, parallel bones – legs. Digging again, I found a 5-inch-thick wafer, with bluish-gray cloth and a line of eagle buttons, and what I thought were ribs and underwear.”

“A soldier had been buried in a pine box, and the ground had collapsed on him and compressed it into a wafer,” continued Ambrose. “I told my friend that I was digging with, and he laughed, saying it was a trash heap with chicken bones. I dug again, and a skull with all its teeth rolled out.”

Ambrose then covered the site with tin cans and trash so others wouldn’t dig there and notched a nearby tree so he could find it again. “I felt bad for disturbing a grave, but I didn’t want the soldier bulldozed, so I notified Fairfax County,” he said. Red tape and paperwork ensued and, 2-1/2 years later, the land sold and McDonald’s planned to build there.

“Luckily, Dr. Owsley was available to come here,” he said. By then, leaves and pine needles had camouflaged the spot but, using his metal detector, Ambrose found it. “They excavated and the bones came up,” he said. “Owsley used his probe and found five more graves in a row. The whole community became involved in this mass effort, and I dug beside Owsley and Mike Johnson, [the county Park Authority’s senior archaeologist], for three days.”

Ambrose said the skeletons were well-preserved and the graves were shallow because the original diggers hit shale and couldn’t dig deeper. “The big question was, ‘Who are these guys?” he said. “They all had standard, Union buttons, plus shoulder buttons most Civil War uniforms didn’t have. One soldier wore a canvas-topped, baseball shoe, so we thought it was a city unit. One had a musket ball in his pocket, and they’d died of bullet wounds.”

The Smithsonian’s forensic analysis revealed they’d eaten a seafood diet so were, perhaps, from New England. It also showed most were 23 or younger, the youngest just 16-18. “Dalton Rector researched and learned one guy was on a club baseball team in Boston,” said Ambrose. “The soldier I found was Albert Wentworth, who was 17, but lied about his age – you had to be 18 – to join the war.”

DNA testing was impossible due to lack of close relatives, so the remains stayed at the Smithsonian for nine years. But Rector plugged away, eventually identifying them.

USING FORENSIC EVIDENCE, genealogical records and extensive historical data, he determined the soldiers were from the Massachusetts unit. Some of the jacket buttons had an "I" on them, signifying infantry, and Massachusetts officers wore this type of button.

Companies G and H of the 1st Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment fought in the Battle of Blackburn’s Ford, and Rector obtained a list of those soldiers’ names and ages, learned how each man died and painstakingly concluded which ones were in the Centreville graves.

Company G’s soldiers battled in their jackets. But during hand-to-hand combat, Company H joined as reinforcements, fighting without jackets. That’s significant because the men in graves No. 1, 3 and 6 all had jackets, but the others did not. Besides Wentworth, the other soldiers were 1st Sgt. Gordon Forrest, 32, and Pvts. Thomas Roome, 31; James Silvey, 23; William Smart, 21 and George Bacon, 22.

Hearing the news, the Massachusetts Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War called the Park Authority to arrange for their return home. Johnson and Park Authority volunteer C.K. Gailey personally drove the remains there. And on June 10, 2006, the soldiers were buried with full military honors in the Massachusetts National Cemetery on Cape Cod.

It was an authentic re-enactment of a burial from the Civil War period. It included a horse-drawn hearse, a procession to the burial site led by a fife-and-drum corps, an 1879 prayer and a 21-gun salute with 1853 Enfield rifle muskets. The six soldiers were each buried inside the same type of pine caskets used when they were killed.

Covering each casket was a 35-star, American flag like those in 1861. The honor guard then folded the flags into triangles and presented them to particular people, including Johnson. He later gave it to Frey, who displayed it in the Sully District Governmental Center.

On Saturday, Lewis said the flag is still there. He, Frey and others then unveiled the marker to be placed on a grassy spot near the McDonald’s parking lot. “It will enable all to enjoy this memory,” said Lewis. Then the Rev. Drew Pallo said, “Now we bring closure to those who brought this story to light.”