Tom Johnston of Countryside had been unaware that the golf course where he was practicing his putting Sunday afternoon was also an official wildlife sanctuary.

About two weeks ago, the Audubon Society certified both the Algonkian and Brambleton golf courses as Audubon Cooperative Sanctuaries. Owned and operated by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority (NVRPA), they are the first two publicly owned courses in the state to achieve this status.

"That’s perfect," said Johnston, standing on the Algonkian green. "It would be nice if this whole strip of land were designated," he said, adding that he frequently hikes in the area, along the Potomac River. He said the new Bermuda grass on the fairway seemed to grow in faster and fuller than the previous turf, although he noted that its quality would not be known until next year.

The existing wildlife on the course, he said, "sort of adds to the experience."

"WE’VE HAD quite a few people say the Bermuda grass is going to be a nice way to go for the golf course," said Algonkian Park manager Mark Whaley, adding that a few golfers who had seen that the course was now certified had complimented the effort.

Assistant Park manager Roy Geiger pointed out that it is especially important for Algonkian and Brambleton golf courses to be environmentally friendly, as the former lies along the Potomac River and the latter next to Beaver Dam Reservoir.

Park Authority executive director Paul Gilbert said the parks had been working to attain certification for about a year and a half. "We’re really excited about this," he said.

Gilbert said changes to the courses would make them more attractive and also more playable, as well as giving golfers the satisfaction of contributing to an environmentally conscientious organization.

"Not all golf courses have been good for the environment in the past," he said, but he noted that testing had indicated that water flowing off the courses was now cleaner than water flowing onto them.

To become certified, the courses had to meet criteria for water quality, conservation, providing habitats and educating the public. The man who brought them up to standards was course superintendent Bryan McFerren.

McFerren said Algonkian’s new Bermuda grass, in contrast to the annual bluegrass and ryegrass that previously covered the fairway, requires no fungicides or other pesticides, does not need as much watering and has a shorter mowing period. He said the money saved on fungicides alone would make up the cost of resodding within two years or so. Brambleton’s fairways, however, are sodded with bent grass, which is heartier than Algonkian’s previous turf.

THE BERMUDA GRASS also is "at its best" in July and August, when other grasses are most likely to succumb to diseases, said McFerren. However, he said, it does spend more of the year in dormancy, so golfers who want a green fairway can go to Brambleton in late fall and early spring.

Both courses have adopted several policies that make them more environmentally friendly. McFerren said park employees no longer apply fertilizers or other chemicals within 20 feet of any pond or creek and do not mow near water that isn’t on the play area.

Many plots that are not part of the fairways but used to be mowed anyway are now being left to grow into meadows that will feed and harbor local wildlife. At Algonkian, some of these plots have been planted with wildflowers that will attract honeybees and butterflies, as well as deer. McFerren said that the unmowed areas will mean less gasoline burned and carbon dioxide released by lawnmower engines. The new no-mow areas amount to about seven acres at Algonkian and three or four acres at Brambleton, he said.

Certain areas have been designated wild and marked with "Do Not Enter" signs. "These are areas where, if you hit your ball there, you wouldn’t really want to go in anyway," said McFerren, noting that most of the spots are swampy.

Birdhouses and designated brush piles also provide wildlife habitats, as do dead trees, so long as they are not deemed hazardous. McFerren said increased hand watering and the use of sprinklers that only rotate 180 degrees near bodies of water would reduce water usage.

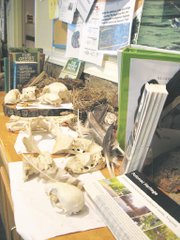

AS FOR EDUCATING the public, he said signs have been placed on the courses to let visitors know what kinds of trees and other wildlife they are looking at, and a few miles of trail, complete with interpretive signage, have been built at Algonkian and are underway at Brambleton. The Park Authority’s chief naturalist will host a nature walk at each park in the spring. Algonkian also boasts an informational nature kiosk in its clubhouse.

"We want golfers to really get an experience on the golf course, beyond just a round of golf," said McFerren.

Gilbert said the changes reflect the Park Authority’s new mission statement, which changed in recent years from setting a goal of acquiring and building parks to one of conserving natural and cultural resources and fostering people’s understanding of their relationship to the environment. The NVRPA’s other golf course, Pohick Bay, is expected to achieve Audubon certification in the next few months.

Fourteen of the state’s privately owned courses have been certified.