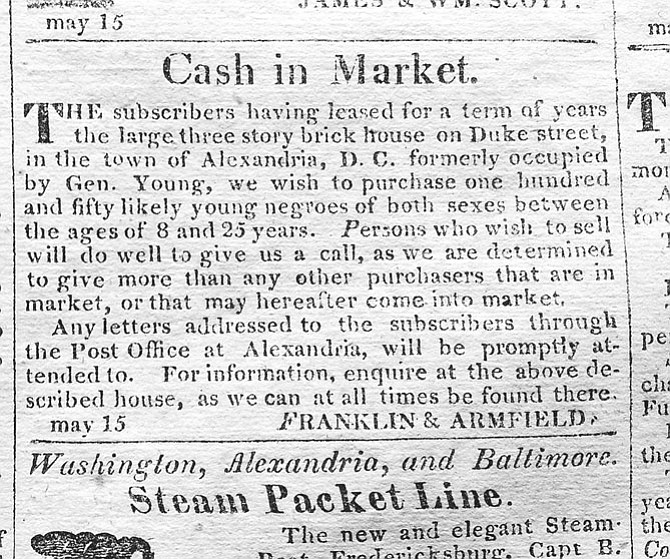

Alexandria — On May 17, 1828, the following advertisement appeared in the Alexandria Phoenix Gazette:

Cash in Market~

The subscribers having leased for a term of years the large three story brick house on Duke Street, in the town of Alexandria, D.C. formerly occupied by Gen. Young, we wish to purchase one hundred and fifty likely young negroes of both sexes, between the ages of 8 and 25 years. Persons who wish to sell will do well to give us a call, as we are determine to give more than any other purchasers that are in market, or that may hereafter come into market. Any letters addressed to the subscribers through the Post Office at Alexandria, will be promptly attended to. For information, enquire at the above described house, as we can at all times be found there.

This was neither the first nor the last such notice to appear in Alexandria or Washington newspapers, but it commenced the business operations of the most successful interstate slave-trading operation in the history of the United States. Over the next eight years, John Armfield in Alexandria purchased from local planters and farmers, and shipped to his partner Isaac Franklin at New Orleans at least 5,000 Virginia and Maryland slaves. Franklin and Armfield, as the firm came to be known, were engaged in the transportation and sale of slaves within the United States; in compliance with the law, they did not bring into the country any African or West Indian blacks.

The international slave trade involving all the major nations of Europe as transporters, much of Africa to supply the slaves, and both North and South America and the West Indies as markets for the enslaved blacks had begun in the middle 15th century and continued in Cuba and Brazil until nearly the middle of the 19th century. In all, between 10 and 15 million blacks were forcibly transported across the Atlantic Ocean. Of this number, fewer than 400,000, barely 4 percent, were imported to all of British North America. Nevertheless, this 400,000 was sufficient to establish racially based slavery in every British North American colony, a situation which persisted in all of the new American states at the time the federal Constitution was adopted. The Constitution, reflecting the needs and desires of Carolina and Georgia, prohibited interference with the importation of slaves by the federal congress until 1808, a period of 20 years. The need for such a prohibition is ample testimony of the inclination of many of the founding fathers to restrict the slave trade at the earliest possible date.

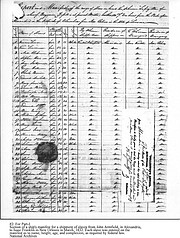

Indeed, George Mason, of Fairfax County, opposed the ratification of the Constitution by Virginia because (among other issues) it allowed this "infamous traffic" to continue for another 20 years. The importation of blacks into the United States barely survived the 20-year protection provided by the Constitution. On March 2, 1807, Congress prohibited further importation of slaves after Jan. 1, 1808. This same legislation expressly allowed the interstate transportation of slaves providing that duplicate copies of manifests listing slaves transported should be kept and certified by U.S. Customs officials. Thus, Franklin and Armfield operated within the law of the United States.

In fact, this statute, by prohibiting importation of slaves, yet allowing the interstate transportation of slaves, combined with a surplus of slaves on the worn-out tobacco farms of Virginia and Maryland and a need for more slaves to operate the newly developing cotton and sugar plantations of the deep South (Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama, east Texas), a need which could be supplied in no other way, acted to create the interstate trade which was so profitable for Franklin and Armfield.

Location on the Potomac River, in the heart of a region with many surplus slaves, made the City of Washington and the town of Alexandria an early transfer point for buyers and sellers of enslaved African-Americans. As early as 1802, an Alexandria grand jury had complained of the "Grievance ... of persons coming from distant parts of the United States into this District for the purpose of purchasing slaves." It referred to the "wretchedness and human degradation" of marching black slaves "in our streets ... loaded with chains as though they had committed some heinous offence against our laws." It lamented that "interposition of civil authority cannot be had to prevent parents being wrested from their offspring, and children from their parents, without respect to ties of nature."

IN 1816, vituperative Virginia congressman John Randolph declaimed against this "nefarious traffic" in the House of Representatives and insisted it was not necessary that "this city should be made a depot for slaves." Yet the newspapers continued to carry advertisements for the local traders. Samuel J. Dawson, Jesse Bernhard, and Samuel Meek advertised to buy in Georgetown; John W.Smith and E.P. Legg were among those who operated at Alexandria. By the 1830s, James H. Birch, William H. "Yellow House" (from the color of the building where he conducted his business) Williams, and Joseph W. Neal and Company bought slaves in Washington City, as did numerous planters who came to buy for themselves. Alexandria was soon recognized as "the best point from which to start both coastwise shipments and overland coffles.'' It became "the place most favored" for beginning such journeys.

Isaac Franklin was operating as a slave trader in Mississippi as early as 1819. In 1824, he met John Armfield driving a stage in Virginia. Armfield later married Franklin's niece and, in 1828, the two men formed a partnership to engage in the slave trade. John Armfield, who operated the Alexandria end of the business, was a careful and successful businessman. He, like his partner Franklin, is reputed to have made over half a million dollars (in 19th-century value) in the slave trade. How then did this business operate in the City of Alexandria?

John Armfield purchased slaves at the firm's "establishment" on Duke Street from 1828 until 1836. He not only purchased slaves brought to him by farmers and planters, but had agents or buyers at Richmond and Warrenton in Virginia, and at Baltimore, Frederick, and Easton in Maryland. The majority of the slaves were transported to New Orleans by ship from October through April of each year.

THE FIRM initially used whatever ships were available such as the Shenandoah of Georgetown and the Ariel and James Monroe of Norfolk, often sharing these ships with other traders. By 1834, they owned four ships of their own; the United States, the Tribune, the Uncas, and the Isaac Franklin, which was built at Baltimore especially for their trade. The ships sailed from Alexandria once a month at first and later once every two weeks. A typical cargo was from fewer than 100 slaves to more than 250, the average being a little less than 200. Once a year, during the summer, they transported slaves by "coffle," or chain gang, overland to Mississippi.

The best descriptions of Franklin and Armfield’s Alexandria "establishment" come from abolitionist writings of the early 1830s. Many abolitionists came to Washington to protest slavery and the slave trade before the Congress, and several of these men came across the river to Alexandria, inspected the slave "prison or jail" on Duke Street, and recorded what they saw. By this time, Franklin and Armfield were at the height of their business.

The Rev. Joshua Leavitt of New York visited the "establishment" in late January 1834. Leavitt had been told that Armfield "bore the character of a gentleman, of fair character for integrity and openness in his dealings, and one who was ever ready to afford any facilities forredressing whatever abuses might grow out of the nature of his business." George Drinker, an Alexandria Quaker and abolitionist, confirmed this essentially positive picture of Armfield and added that Armfield was very careful to avoid purchasing or transporting free blacks, and often went "to much trouble and expense ... to keep his business free from every thing that would contravene the laws."

The following year, 1835, a Boston abolitionist, Professor E. A. Andrews, recorded that Armfield had by his efforts to prevent kidnapping and his honorable mode of dealing "acquired the confidence of all the neighboring country." In fact, Andrews had been assured that this reputation extended even to the Alexandria slave community, and that when faced with being sold, many Alexandria slaves requested that they "be sold to Mr. Armfield.” Even so, trading in the buying and selling of other human beings was at all times a nasty and disreputable business.

Four-part Series

See the entire four-part series as it appeared in the Alexandria Gazette Packet by clicking the link below:

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade

Or read each part online by clicking the links below:

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part I

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part II

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part III

Alexandria to New Orleans: The Human Tragedy of the Interstate Slave Trade, Part IV