Food trucks took three steps into Alexandria following a City Council meeting on April 16, but an April 25 Parking and Transportation Board hearing may have set them two steps back.

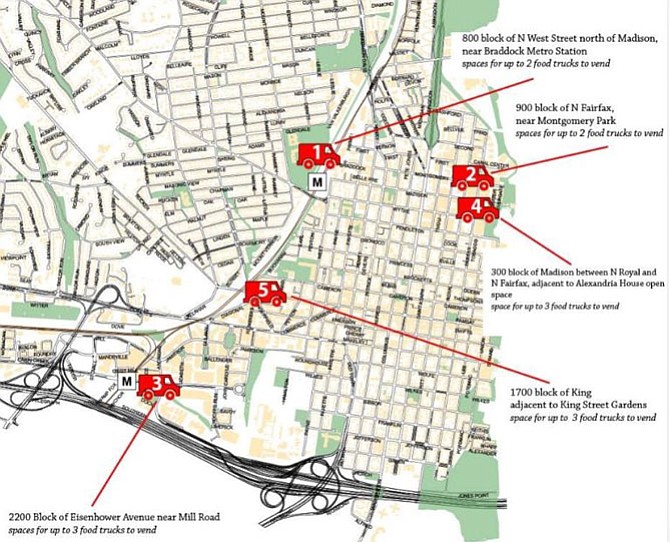

The council had approved food trucks to move into Alexandria with the locations to be determined. Staff proposed that the trucks be allowed to park at the Braddock, King Street, and Eisenhower metros, as well as two locations in north Old Town. But at the Traffic and Parking Board, skepticism on the board about the proposal’s impact on parking led to the elimination of the two Old Town North sites.

The proposal follows the two year-long pilot program that allowed food trucks to set up shop in various parks and city properties around the city. However, the program saw poor participation due to the heavy restrictions. City staff hope new allowances for food trucks to park around the city will boost participation in the program.

But even before the comment was turned over to the public, members of the board expressed concerns about general food truck issues. Jay Johnson, for instances, argued that eight hours was too long to allow food trucks to stay on the streets, both out of the possibility that they’d be blocking the rush hour traffic home and that they’d be cutting into the local restaurant dinner hours.

While the conversation was ostensibly about the impact of the food trucks on parking and transportation, many business owners and private citizens expressed fears that the food trucks would destroy the community.

“They will be right across the street,” said Michael Naieri, owner of A La Lucia, which sits almost directly across from the Madison Street location. “The businesses in Old Town are already suffering, this is not going to help. We pay rent and taxes, and this hurts us.”

Rebecca Beard, a manager at A La Lucia, said that the food trucks would not only poach their business, but take up parking that customers already say is scarce.

“It’s not conducive to the community and not conducive to local business,” said Margaret Townsend, president of the Old Town North Community Partnership. “We’re opposed to the ones in Old Town North, but throughout the city we don’t think we have enough parking for this.”

The exclusive possession of the parking spaces in North Old Town upset more than just the local restaurants. The Art League sits across from the food truck location on Madison Street, and Art League executive director Suzanne Bethel said that many of her students are carrying heavy equipment to the studio and need to be able to park nearby.

The board made special note of a suggestion by local resident Engin Artemel, who suggested that this discussion should have been part of the Old Town North area study, which specifically analyzes parking needs in that neighborhood.

BEYOND TRANSPORTATION, one source of discomfort for the board was concerns about the outreach process used by city staff called AlexEngage. The survey, managed by an outside group called Peak Democracy, received over 2,375 responses, the largest in the history of the program. However, Peak Democracy uses an algorithm that sorts responses into several categories, one of which is listed as “uncivil.” The reasons for this categorization can be unclear, said Assistant City Attorney Joanna Anderson, but one way or another: over 500 responses, a quarter of those who responded, were listed as uncivil.

One of the possible reasons for exclusion would be too many responses within a narrow window of response, or multiple answers from the same IP address, but Darrel Drury, president of the north Old Town civic activist group VISION and former professor of advanced quantitative methods and research design at Yale University, said that response window lines up with when his organization sent out an email to their membership telling them about the survey.

At the City Council meeting on April 16, Anderson included a chart with both of the numbers at the end of her presentation, but during the discussion only referenced the numbers with the 500 responses excluded when she argued that the majority of the survey responses were in favor of allowing food trucks.

“We didn’t leave the information out,” said Anderson. “We needed [City Council] to know, in full transparency, that we did get this information from the vendor. There are a lot of questions out there. The safest course was to present them both.”

Anderson said that the council had access to both of the sets of numbers in the presentation. Anderson also downplayed the role of the survey in the final decision, noting that it’s a means of gathering public feedback but that it’s not a scientific measurement and that it’s just one piece of information. But for Drury, the survey is vital, arguing that it proves a systematic bias against the local residents. Drury argued that arguable exclusion of the 500 results touches on the deeper ethics issues of the city that exist beyond the levels of individual conflicts of interest.

While the board included their concerns about the process, parking was the issue that ultimately doomed the two north Old Town locations. For some on the board, the two issues were interconnected.

“I don’t understand how there is such an enormous gap between staff saying that [parking] is not an issue and everyone’s experience that it is,” said board member William Schuyler.

“We need to be able to feel a confidence in that data,” said Ana Tucker. “We need to be able to trust that.”

Though the decision was based around parking, the input from local businesses had an influence on the board.

“We’re hearing an obvious story about these locations,” said board member Melissa McMahon. “The small area planning process going on there now, that would be to raise these issues. I don’t want to put a big X on the future for food trucks, but I don’t want to detriment the local businesses either, so I don’t recommend those two [North Old Town] sites.”

McMahon suggested, in the future, that staff speak with Arlington businesses to find out about the impact of food trucks on businesses there. Rosslyn and Old Town are different sites in a lot of ways, but Mary-Claire Burick, president of the Rosslyn Business Improvement District, said in an email that the reception to food trucks in that area has been well received by customers and that businesses had learned to live with it.

“With the consumer in mind, the Rosslyn BID worked in close partnership with Arlington County, property owners, restaurants, and food trucks to develop and launch a mobile vending pilot project that we think benefits everyone,” said Burick. “Consumers have safe, convenient access to more food options; Food trucks have a guaranteed place to park (removing uncertainty); and owners of brick and mortar restaurants are able to retain easy access and visibility for their customers. So far, we’ve received positive feedback from consumers. The BID conducted an online survey of the zones in late 2015 and found that a majority (69 percent) of respondents approved.”

Najiba Hlemi from the Food Truck Association said she was also disappointed with the process, but in that she’d hoped the city would consider zones of allowable food truck locations rather than specific parking spots. Hlemi said the association was grateful to the three locations that trucks would now be allowed to sell in, though she was still disappointed with the perception of an anti-food truck bias on the board, especially after City Council had been so approving of the plans.

“The board made their decision on what is best for the businesses,” said Hlemi, “but they shouldn’t be able to decide who gets to compete. That’s for consumers to decide.”

The day after the meeting, Mike Tam, catering director for Perfect Pita, said he was satisfied with the two locations being taken out of consideration. Tam said the store in Tysons Corner had to deal with a food truck vending illegally across the street, which was eventually moved into a nearby lot, but when Gov. Terry McAuliffe lifted the ban on food trucks from state-run roads in 2015 the truck was back out across the street and the store’s business hasn’t recovered. At the King Street location, Tam says he isn’t as concerned because there’s already competition in the area, and the food truck might even bring new business to the area.

“But here it would be tripling our competition,” Tam said, pointing across the street to the parking space that could have been filled with a food truck. “I breathed a sigh of relief when I heard.”