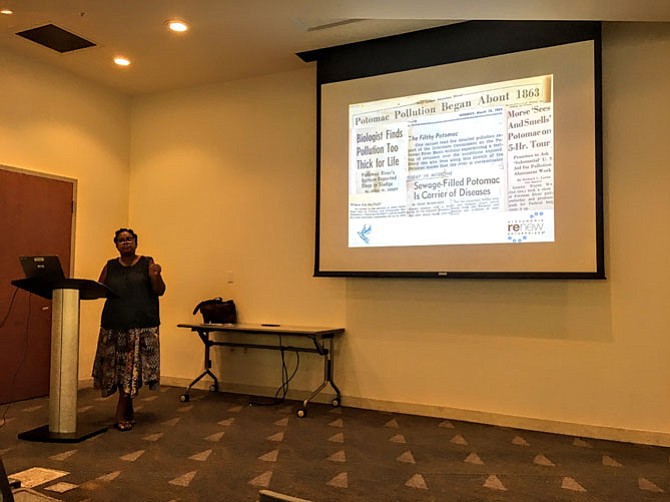

Jae Watkins, community outreach and education manager for Alexandria Renew Enterprises, explains Alexandria’s history with wastewater treatment. Before the city commissioned a public utility to clean dirty water, wastewater flowed into the Potomac River unsanitized. Photo by Antonella Nicholas/Gazette Packet

Last weekend at Shirlington Branch Library, residents had the opportunity to learn about how wastewater is treated in Alexandria from Jae Watkins, community outreach and education manager for Alexandria Renew Enterprises.

Alexandria Renew is a public water recovery utility and cleans the City of Alexandria’s water.

Watkins began the lecture with a recap of wastewater treatment history. There has always been wastewater, but wastewater treatment has only been around since the 1800s. In Alexandria, when scientists discovered that contaminated water made residents sick, wastewater was routed to Hunting Creek and the Potomac River.

The larger the city, the larger its sewage. “As Alexandria grew, local water started to show wear and tear,” Watkins said. The Potomac River, especially, was congested with sewage contamination.

In 1952, the City Council created the Alexandria Sanitation Authority to address the city’s problem of contaminated water. It became Alexandria Renew in 2012.

Alexandria Renew prides itself on its integration into the community. Located in the East Eisenhower area, the architecture of the facility blends into its surroundings — even though the facility processes all sorts of sewage, the refuse is not visible to passersby. “When you walk by, you don’t smell us,” Watkins said.

The facility has a small footprint, which Watkins says makes it more innovative. Most water treatment facilities are laid out horizontally, but Alexandria Renew has a vertical construct to maximize space for the water treatment process.

When you take a shower, flush the toilet, or use the sink, washing machine or dishwasher, the dirty water, or “wastewater,” flows out of your home through the sewer to Alexandria Renew’s water treatment facility. On a given day, the facility processes around 30 to 35 million gallons of wastewater.

The seven-to-eight hour process begins with screening out heavy items from the wastewater. Then, as more junk sinks to the bottom, fats, oils, and grease are pushed out. The remaining water is then pumped to Biological Reactor Basins where naturally occurring microorganisms eat nitrogen, phosphorous and other pollutants. Next, water is disinfected by UV lamps in order to prevent the microorganisms from reproducing. The clean water is finally released into Hunting Creek, which flows into the Potomac River.

Alexandria Renew keeps an eye on the levels of phosphorous and nitrogen in the water that is returned to the Potomac River because the Chesapeake Bay, the body of water into which the Potomac flows, is sensitive to these elements. If levels become too high, algae invades the water, seizing the oxygen that the Bay’s natural organisms need to survive.

Besides transforming wastewater into clean water, Alexandria Renew takes the solids found in the wastewater and removes dangerous pathogens through pasteurization and other procedures. The result is a “biosolid” rich in nutrients that serves as an organic fertilizer to farms across Virginia. Using this recycled material, farmers do not have to rely on chemical fertilizers.

Environmentally conscious citizens attended the lecture, some of them Arlington residents since it was held in Shirlington. Among them was Arlington resident Priscilla Lujan. Lujan’s concern and skepticism about the status of the nation’s environmental agenda, especially in view of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, spurred her attendance. “Since Flint, I worry about the water and non-scientists in the government,” she said.

Irene John, also an Arlington resident, came because she has taken an interest in energy conservation efforts. John had seen a water treatment facility on Glebe Road and wondered what goes on there. “It’s about getting a better understanding of the community,” she said.

The Glebe Road facility is Arlington’s Water Pollution Control Plant, and although it is not operated in the same way as the Alexandria Renew facility, the water undergoes similar treatment.

Arlington resident Ryan Weir also attended the lecture and believes that the cleanliness of water should be a priority, not only for city and county governments, but also for citizens. “It’s important that we’re not polluting it,” he said.

Watkins agrees with these residents and admires the efforts of Alexandria Renew and the city to keep Alexandria’s water treatment system up-to-date and effective. “Investing in water infrastructure keeps us healthy,” she said.

There are items, however, that Alexandria Renew is not capable of processing, namely medicine, grease, and wipes. “Don’t flush medication,” Watkins said. She cited the city’s handful of “Drug Take Back” events where residents can safely dispose of expired medication. As for grease and wipes, they should be discarded to go to a landfill.