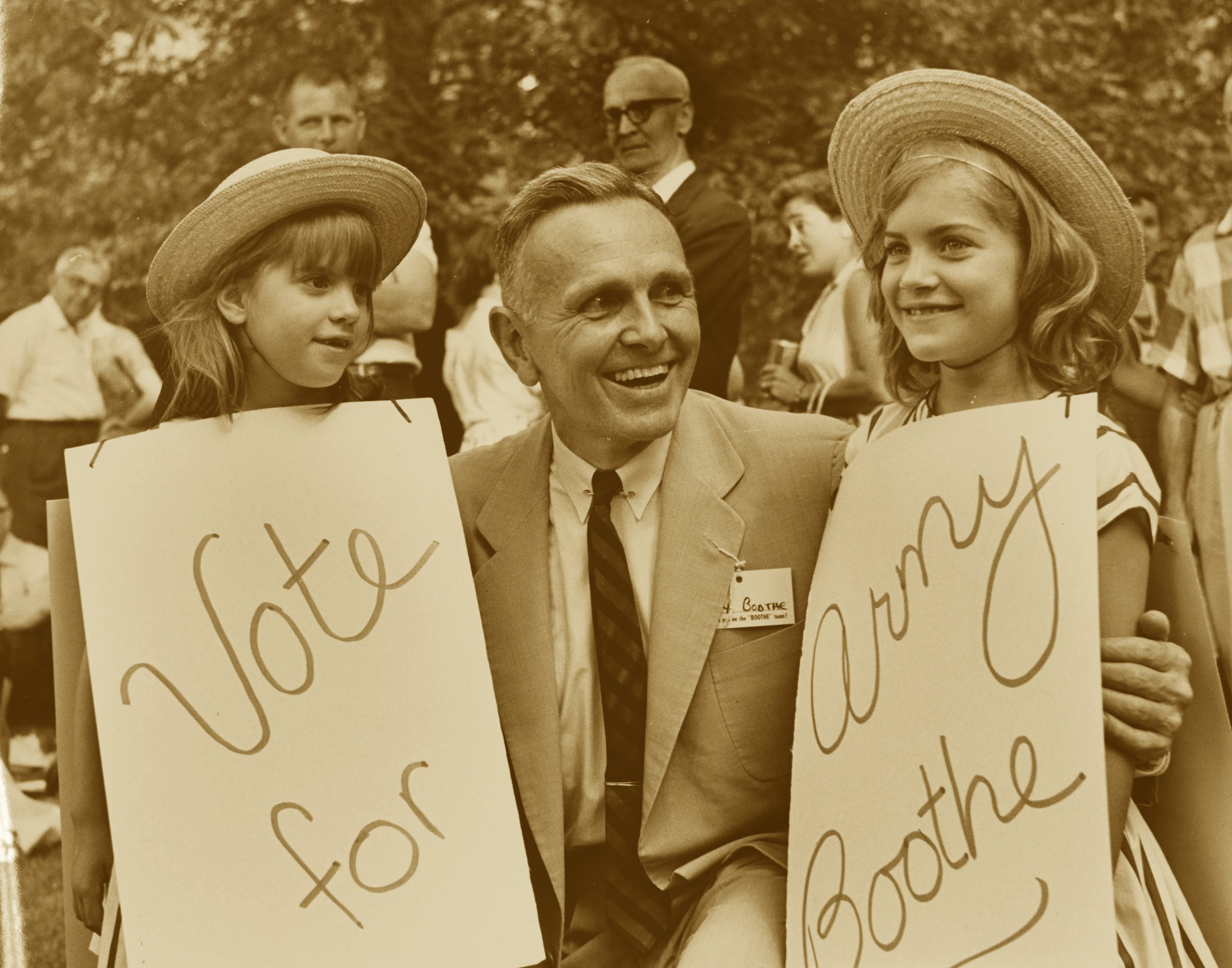

The Young Turks, left to right: Armistead Boothe of Alexandria, Stuart Carter of Botetourt County, George Cochran of Staunton, Griffith Dodson of Roanoke, Walter Page of Norfolk and Julian Rutherfoord of Roanoke.

His actions in the coming decades in the House of Delegates and the state Senate would shape the forces of history by pushing back against the Byrd machine to increase state funding for public education and slowly dismantle Jim Crow institutionalized racism.

A native of Alexandria, his father was president of the First National Bank in Alexandria and leader of the Democratic Party. Boothe graduated from Episcopal High School and the University of Virginia before becoming a Rhodes Scholar studying law at Oxford University. From 1939 to 1942, he served as city attorney of Alexandria although he resigned that position to become a naval air combat intelligence officer in the Pacific Theater during the war. Like many other young war vets of the era, Boothe ran for office in the election of 1947.

"The Young Turks — it's not known who put that tag on them — represented something so far as recent legislative sessions are concerned," explained Richmond Times-Dispatch political reporter James Latimer. "They generally were within the organization, yet didn't hesitate to challenge its dictums."

Boothe was leader of the pack, which included Stuart Carter of Botetourt County, George Cochran of Staunton, Griffith Dodson of Roanoke, Walter Page of Norfolk and Julian Rutherfoord of Roanoke. As a group, they were able to force a vote on a resolution to allow a referendum on Virginia's controversial poll tax.

It was a relic of the Jim Crow era that didn't seem to make sense anymore, although the Byrd Machine relied on the poll tax as a way to perpetuate its power. The Senate Privileges and Elections Committee killed it with a five-to-four vote, but it was clear the group was wielding a new sense of power inside of a rickety old machine.

"I shook the tree, but somebody else picked up the apples," said Delegate Robert Whitehead, leader of the liberal faction of House Democrats.

Perhaps the greatest claim to fame of the Young Turks was a budget standoff that literally stopped the clock, pausing the hands of time in the House chamber at 11:22 pm to prolong the session past the witching hour. At issue was a $1 million appropriation to give teachers a pay raise of $50 a year. For a state that was famously stingy with funding public education, it was a move that signaled new priorities for a new era. In a late-night confrontation, one of the senators threatened Delegate Dodson of Roanoke.

"One well-known senator went so far as to warn him that his father would lose his job as clerk of the House unless Dodson switched his vote," explained historian Peter Henriques. “Such pressure simply made Dodson firmer in his opposition to the governor's budget."

Governor John Battle called all of the Young Turks into his third-floor office at the Capitol one by one, twisting arms and laying on the pressure late into the evening. Shortly after 3 a.m., the Young Turks lost and the raises for teachers were rejected. Undoubtedly, the delegates were tired and exhausted. But they could declare a kind of victory by bringing attention to the racist poll tax and the retrograde education spending. Their efforts certainly caught the attention of editorial boards and reporters.

"The group, full of something akin to college spirit and often better organized than the leadership, has refused to go stand in the corner," wrote political reporter Charles McDowell in the Richmond Times-Dispatch. "Anybody who hasn't heard them coming has only been listening out of one corner of his ear."

They would meet every night at the Hotel Richmond, directly across the street from Capitol Square. Eventually, they were able to elect more Young Turks to the House and increase appropriations for education. By the mid-1960s, the courts outlawed the poll tax. Walter Page left the House to take a job as a judge in Norfolk. Armistead Boothe and Stuart Carter eventually moved over to the Senate. These days, their greatest legacy is pushing for reform to the Byrd Machine while being active participants of the Byrd Machine.

"I think this is a very healthy thing for the state and for the organization itself," explained Boothe in 1954. "The tree of good government can flourish better if its roots are sunk more deeply in the ground and spread over a wider area, rather than being nurtured from a limited source."

This story is an excerpt from "The Byrd Machine of Virginia: The Rise and Fall of a Conservative Political Organization." You can get a signed copy at the book launch, when author Michael Lee Pope will talk about the book and sign copies. The book launch is 7 pm on Oct. 20 at the Athenaeum, 201 Prince Street.