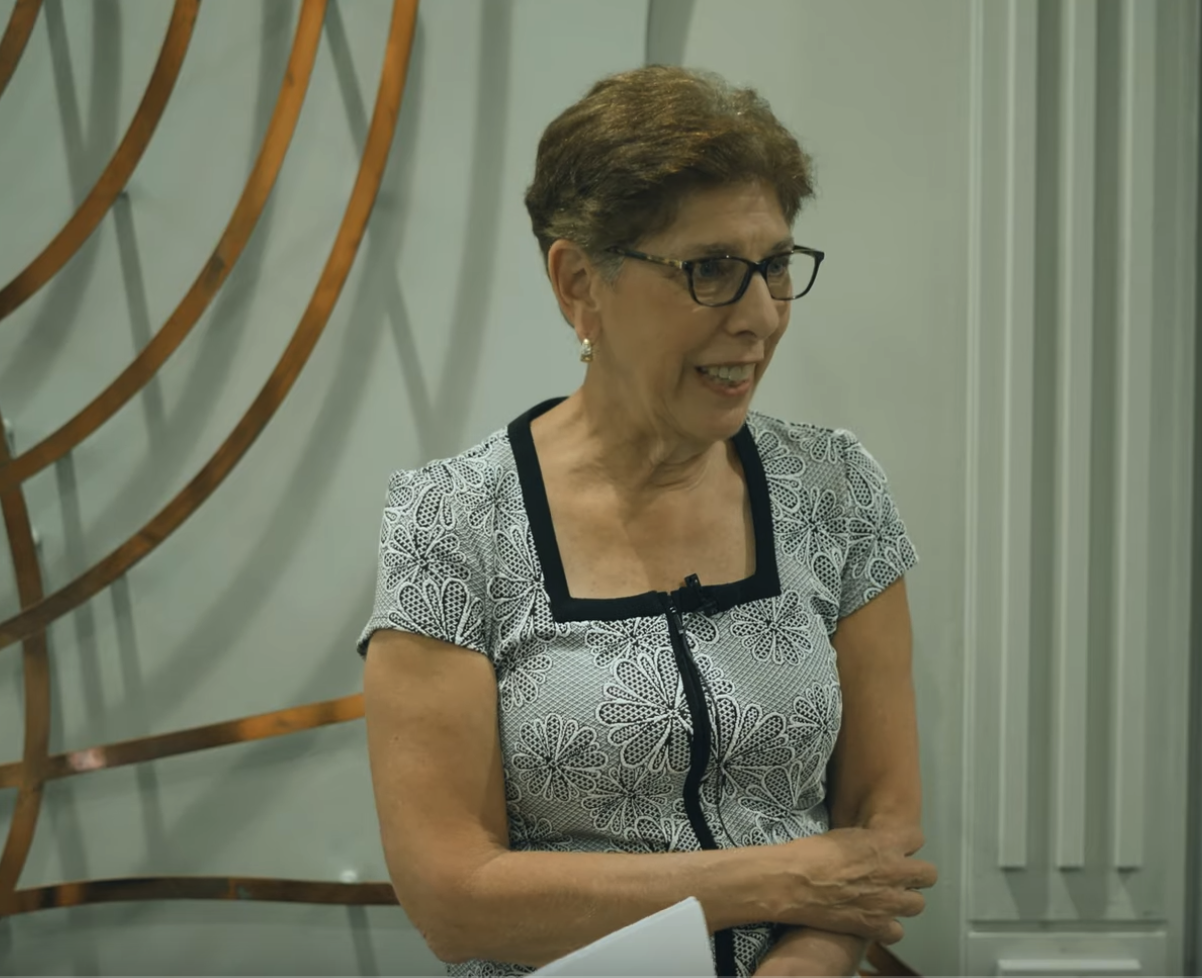

Linda Ambrus Broenniman, a Great Falls resident and author of “The Politzer Saga,” released Sept. 12, sits in her great-grandmother Margit’s seat at the Dohány Street Synagogue within blocks from the Rumbach Synagogue in Budapest, Hungary.

The Politzer Saga by Fairfax County author Linda Ambrus Broenniman, a first-generation American Hungarian, became a reality because of how little she knew about her parents and her quest for truth. "An unwritten rule governed discourse at our house: no question asked," she said in the nonfiction book.

Broenniman is the daughter of research professor Clara M. Ambrus, MD, and Julian L. Ambrus Sr., MD, Ph.D., both practicing Catholics. According to obituary records, her parents emigrated from Hungary to the United States in 1949 after receiving their medical degrees in Europe and working at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. The couple settled in Buffalo, New York, and raised seven children. Clara died in 2011 at age 86 from injuries sustained in a house fire; Julian escaped. He died in 2020 at the age of 95.

Broenniman's father never revealed a secret to Broenniman and her six siblings. Relatives honored the secret until a slip of the tongue by one disclosed that he was Jewish. "My father continued to deflect until his death," Broenniman wrote.

Broenniman’s 243-page work is the culmination of dedicated genealogical research overlaid with the poignant narrative life stories of the Hungarian Jewish Politzer/Misner/Ambrus/Virány family over eight generations. Broenniman tells of "their struggles, their bravery, and their accomplishments. Of their generosity of spirit and remarkable resilience."

Broenniman recently returned from Hungary following the dedication of a permanent exhibition on the third floor of the newly renovated Rumbach Sebestyén Street synagogue in Budapest, Hungary. It is significant because the exhibit is based on the stories in her book, "The Politizer Saga." They are the stories of her family. The exhibition is composed of ten lyrical and artistically rendered seven-minute films.

The Rumbach Sebestyén Street synagogue plays a vital role in Broenniman’s life. The richly renovated Moorish revival synagogue was a deportation point for 20,000 Jews sent to their deaths during WWII. They were eventually sent to Kamianets-Podilskyi in Ukraine, where they were executed.

During the Siege of Budapest in 1945, a bomb damaged the Rumbach synagogue's ceiling, breaking glass windows and damaging the staircase. But the real devastation began in the late 1970s when the roof of the ruined building was torn down, opening it to the heavens. Rain, snow, and birds freely accessed the synagogue. But now, it has reopened as a vibrant multipurpose Jewish cultural center.

The synagogue is only a few blocks from the Dohány Street Synagogue, where Broenniman’s great-grandmother Margit worshipped. Broenniman’s grandfather, Sandor Ambrus, died either on a forced death march or as a Dachau prisoner, Broenniman reported. Her grandmother Bozsi wore black for five years. “When I asked my mother about it, she told me that Bozsi was in mourning,” Broenniman wrote.

Seeing the exhibition for the first time proved difficult for Broenniman.

In an interview on Sept. 15 last week, Broenniman said that in September 2022, she was in Budapest and saw the ten films and exhibit that told the story of the Hungarian Jewish Politzer/Misner/Ambrus/Virány family.

"I was all by myself …. All this grief was able to come out when I saw it by myself, grieving for this family who had suffered so much hardship," Broenniman said. She also felt sorrow for her new friends, part of her journey to this point, András Gyekiczki and László Rajk, who had since died.

Gyekiczki was a disciplined researcher who assisted her efforts. He was "an amazing sleuth." She dedicated her book to him because "without András, this book would not have been possible," she wrote. Gyekiczki held various positions after the fall of the Iron Curtain, including chief of staff to Hungary's Minister of Interior and mayor of Budapest.

Broenniman remembered László Rajk, the Hungarian who directed the ten films. Broenniman never got the chance to meet Rajk in person. "He was an amazing person. He was an architect and a very political figure. He previously collaborated with András on the exhibition “Our Forgotten Neighbors.” And then he started to work on this exhibit," Broenniman said.

In her book, Broenniman describes her childhood as a happy one, "a charmed life." However, secrets about her parents' past came to light in the early 1980s. In a Sept. 2, 2023 video, Broenniman says that her sister Madeline discovered their great-grandmother Margit was Jewish. Afraid of diving into the unknown and shaking up her world, Broenniman did nothing.

The secrets persisted, and neither her parents nor grandmother Bozsi would discuss them. They became the willing keepers of her father's secrets, concealing his Jewish ancestry. Broenniman wrote in her book that her entire family, including Grandmother Bozsi, attended Catholic church every Sunday.

Broenniman traveled to Budapest with her mother and father in 2006. Clara was named "Righteous Among Nations" by Yad Vashem, Israel's Holocaust memorial, among those non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. Her mother, who had advanced Alzheimer's disease, could not deliver the remarks, so her father did.

"He omitted a vital fact," writes Broenniman. Julian survived WWII by escaping from a Nazi slave labor camp and finding refuge from the Nazis with Clara.

Broenniman's search for the truth gathered momentum about five years after the fire that claimed her mother’s life. In 2018, her sister, Madeline, discovered a cardboard box from the fire and sent it to her. Broenniman says she pulled out a marble composition book titled "Our Family Tree," written in English. Gabor Virany, her father's cousin, wrote it, she believes. Other documents were in Hungarian and German. Using a Microsoft translator, she read the birth, death, and marriage certificate names.

Broenniman needed far more than just a translator. She writes in her book, "I needed someone who understood historical context and significance." She is introduced to Anna Bayer, a local Hungarian Jewish expat, who introduces her to Gyekiczki.

On Sept. 2, 2023, Broenniman returned to Budapest. She climbed the steps to the doors of Rumbach synagogue and made her way to its second floor to speak during the dedication celebration of the exhibition and the release of her book.

The screening room again displayed the permanent exhibit of ten films depicting the Jewish Politzer family's fate from the 18th century to the present day, spanning eight generations. Broenniman is not alone, as she was last year.

Broenniman is with her Jewish family and supporters. After years of diligent research, Broenniman established that she and the rest of her family are descendants of the Politizers. Broenniman is Abraham Polizer's great-great-great-great-granddaughter.

She says to the gathered crowd, "I will never know why my father kept his secrets, and it's tempting to judge him for hiding his Jewish roots, and I admit that I was angry when I found out. That anger is gone now that I know the truth. My father was a remarkable and complicated man."

"It's unbelievable that I'm standing here sharing with you the story of my family, and it's a family I never even knew existed," Broenniman says.

Broenniman tells how she and Gyekiczki collaborated for over a year before he shared their findings with Shiza Torney, director of the Hungarian Museum and Archives. It corresponded with the timing of the synagogue's restoration. Gyekiczki asked Broenniman if it was acceptable to have their family stories displayed. "I approved; he wrote the proposal; it was accepted, and here we all are," she said.

Toward the end of her book, Broenniman presents her beliefs on why her father renounced Judaism. He could not hide his Hungarian accent in America, but he could hide his religious heritage.

"He did not want to face intolerance again. He chose to keep his Jewish roots secret from everyone, including his children. He had created an identity he would not or could not let go. He would protect it at all costs."

Broenniman, who currently lives in Great Falls, brought the stories of her Jewish family to light and honored their memories. There is a Jewish expression. "May their memories be for a blessing." Readers can access the short videos of the ceremony, the exhibit, and the Rumbach Synagogue in Budapest on two YouTube videos: https-//www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bmg1_gUCZxE.webloc (three minutes) and https-//www.youtube.com/watch?v=FYFv8uchqL8.webloc (twelve minutes).

https://politzersaga.com/