On Feb. 10, 210 enthusiasts gathered to celebrate Pohick Episcopal Church’s 250th anniversary at a symposium and gala at Mount Vernon. Multiple speakers recounted that the church, known as “the Mother Church of Northern Virginia,” was the first permanent church in the colony to be established north of the Occoquan River, sometime prior to 1724, in Truro Parish. “Its history is as rich as any church in America,” wrote the late Michael Bohn in the Mount Vernon Gazette in 2005.

Pohick Church has been a revered place of worship since George Washington’s day, a target of British raiders in the War of 1812 and a Civil War horse stable and observation outpost. At 9301 Richmond Highway in Lorton, it’s the spiritual home of 500 members today and a national historic site.

The Very Reverend Dr. Lynn Ronaldi, the church’s rector, said that passersby often mistake it for a meeting house or a museum. It is a meeting house, she clarified, “but not a museum.” Having suffered damage and neglect at times, “It has always been resurrected to life,” she told attendees.

Saying “we can all learn from each other,” Doug Bradburn, President of Mount Vernon, observed that the group was “celebrating 250 years of freedom.” The Right Reverend Mark Stevenson, Bishop of Virginia, came from Richmond and commented that the church was “called to be a living temple.”

Sen. Scott A. Surovell presented a resolution from the Virginia General Assembly, noting that the church is a “spiritual haven” and “one of the most historically significant churches in Virginia and the nation.”

Mount Vernon Board of Supervisors’ member Dan Storck gave the congregation a resolution honoring the church’s “centuries-long contributions to our community, American history and for carrying forward the spiritual legacy of its founders to current and future generations.”

Religion and the Revolution

In a pre-dinner symposium titled “Religion in the Age of the American Revolution” and chaired by Dr. Patrick Spero, Executive Director of the George Washington Presidential Library, historians highlighted how religion was a driving force behind the American Revolutionary War. Bradburn said that colonial patriots believed that the “inalienable right of freedom of conscience was given to you by God.” Dr. John Fea said that Americans viewed breaking from England through “a religious lens. God was on the side of the American Revolution.”

Several speakers described George Washington’s evolution that led him to free his slaves in his will. He wrestled with slavery and acknowledged that as a slaveholder, he was a sinner, Dr. Richard Newman said, and “he anticipated the moment of reckoning.” Noting that Washington was a Pohick Church vestryman at age 27, Dr. Ronaldi said, “He struggled and was willing to be transformed.”

The Building

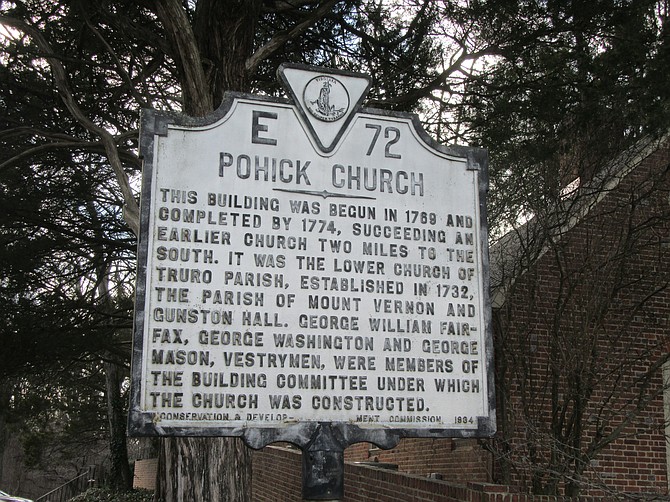

The Georgian-style church, measuring 66 feet by 45 ½ feet and completed in 1774 just before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, is a rectangular, two-story, brick building crowned by a modillioned cornice and hipped roof. It was built by enslaved laborers under contractor Daniel French and probably designed by John Wren because it is similar in design to Christ Church in Alexandria and Christ Church in Falls Church. Building specifications called for bricks to be “well burnt.”

Listed on the Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Places, the 1969 federal nomination noted, “The distinguishing feature of Pohick's exterior is its especially fine stonework, which includes the large quoins at all four corners and the three doorways.”

The churchyard has burials from 1698 to 1957 and a vestry house erected in 1931.

A Storied Church

“The origin of ‘Pohick’ is the Algonquin Indian word for the hickory tree — 'powcohicora,’ which evolved first to ‘pohickory,’ then finally hickory,” wrote Bohn.

The original frame church was built in 1767 close to Gunston Hall. George Mason and George Washington argued about the relocation site; Washington prevailed. Washington, Mason and George William Fairfax were on the vestry and the building committee.

Local wealthy landowners purchased pew boxes and today brass markers bear the names, Washington and Fairfax. The box-like pews were designed to block drafts and retain warmth from heated bricks.

Still in use today is a baptismal font, likely shipped from England where it was used as a mortar in a monastery kitchen in the eleventh or twelfth centuries. The pipe organ, built by Fritz Noack in the 1960s has 880 pipes, 13 stops and 17 ranks.

By 1830s, the church was in great disrepair and “had become so dilapidated that the door to George Washington’s old pew had come to adorn a free black’s chicken house,” according to Fairfax County, a History.

Wars’ Ravages

The British raided the church in the War of 1812, reportedly because of its affiliation with George Washington.

During the Civil War, occupying Union forces stripped the building’s interior except for the crown molding, used it as a stable and used the exterior walls for target practice. Soldiers carved graffiti onto the doorposts. Today’s visitors can see an “M” from that era scrawled on one wall.

Also during that war, Professor Thaddeus S. C. Lowe, an aeronaut with the Union Army Balloon Corps, tracked Confederate movements from Intrepid, his hydrogen-filled balloon, soaring 1,000-2,000 feet above the church courtyard. On March 6, 1862, he reported, “Saw fires at Fairfax Station; some on the road near the Occoquan. This morning cavalry scouts are visible on this side of the Occoquan below Sandy Run.”

The church has undergone several restorations, the last between 1901 and 1916, which returned it to its colonial state.

To Visit

The church is open Monday through Saturday, 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. and Sundays, 12:30 p.m. to 4:30 p.m., following morning services. Group guided tours can be scheduled in advance. Entry is free. For more semi-quincentennial events, visit https://pohick.org/250th/.