That insignificant looking mound of earth that you’ve driven by countless times may be much more than a lump of dirt. At one time, it may have been a significant defense protecting the United States capital. Think of them as the 1860s equivalent of the Department of Homeland Security, an overlapping ring of fire that would threaten any approaching forces. Shortly after the embarrassing loss at the Battle of Bull Run, Gen. George McClellan approved the construction of 48 forts with 300 guns that formed overlapping lines of fire around the capital. Only one of the forts saw action, but those stationed at these forts were always ready to confront invading Confederates.

"It only seems like nothing happened in hindsight," said Wally Owen, curator at Fort Ward Museum in Alexandria. "From their perspective it was quite dangerous, and they thought they would be under attack on several occasions."

Today, most of the defenses are gone, replaced by high-tech video surveillance and no-flight zones. But those with an interest in Civil War history can visit several surviving forts to get a firsthand sense of the Union defense of Washington. All the sites have interpretive markers, although some of the locations will require some sleuthing to find the magazines, bombproofs, wells, gun platforms and parapets. Some amount of imagination will be necessary to visualize the site in its original wartime condition, stripped of vegetation with whitewashed revetments and sodded parapets.

"That any works remain at all is a tribute to the preservationist activists of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the National Park Service and the city governments of Arlington and Alexandria," Owen wrote in the introduction to a 1988 guide to the forts.

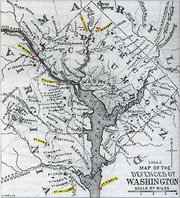

<b>THE DEFENSES </b>of Washington began in August 1861, when Gen. McClellan placed Major John Gross Barnard of the Corps of Engineers in charge of constructing a series of forts, lunettes, redoubts and batteries. Barnard began this process by selecting strategically important locations with little regard for cultivated fields, orchards or dwellings — seizing property in the name of national security. The loss to the Rebels in July at Manassas had created a sense of chaos in Washington, and military authorities recognized the importance of creating a formal defense, especially of the southern approach to the capital. The main forts were placed one-half mile apart, clearing everything in sight for unimpeded visibility.

"It was an interesting sight to witness the simultaneous falling of a whole hillside of timber," observed William Todd, a member of the Seventy-Ninth New York Highlanders. "When all was ready, the bugle would sound a signal, and the last stroke of the axe be given, which brought down the top row; these falling on those below would bring them down, and like the billow on the surface of the ocean, the forest would fall with a crash like mighty thunder."

By the end of 1861, Barnard had successfully completed 23 forts south of the Potomac River, 14 forts and three batteries between the Potomac and Anacostia rivers and 11 forts beyond the Anacostia. But this was only the beginning of the defenses, and many of the forts came later. Fort Willard, for example, was built in 1862 by detachments of the 34th Massachussetts Infantry and named for Col. George Willard, who was later killed at the Battle of Gettysburg. It was a 14-gun, enclosed work with a bombproof on the north wall of the fort and one magazine.

"It was sort of like an advance battery," said Michael Rierson, manager of resource stewardship for the Fairfax County Park Authority. "It could slow the enemy down for a while, but it was just a postage stamp compared to Fort Ward."

<b>FORT WARD OFFERS</b> the best Civil War experience, with a recreated Civil War era fort that was reconstructed in the 1970s. Named for Commander James Harmon Ward, the first naval officer killed during the war, Fort Ward defended the Leesburg and Alexandria turnpike — known today as Route 7. The historic site and museum features military objects, a research library, lectures and numerous living history programs. The museum’s exterior was patterned after the headquarters building at Fort Sumpter, and the restroom facility’s exterior was copied from the headquarters building at Camp Convalescent in Arlington.

"Fort Ward is representative of the development and problems of the defense of Washington as a whole," Owen wrote in the 1988 guide to the defenses of Washington. "Beginning as a hastily constructed fort in the wave of panic after the first Battle of Bull Run (Manassas), it developed into a model field fortification that utilized many of the technological improvements learned during the war."

Other remaining fort sites offer a more peaceful visit, especially the serene Fort C.F. Smith. Named in honor of Major Gen. Charles Ferguson Smith, who died in 1862 of a leg infection aggravated by dysentery, the fort was constructed in 1863 on the recommendation of an 1862 commission. Fort C.F. Smith was built to extend the line of forts to the Potomac River and to command a ravine not covered by the guns of Fort Strong. Much of the fort was preserved because it was part of an estate owned by the Hendry family, who incorporated the earthen mounds into the landscaping of their land.

"You can still basically see what was there," said David Farner, park ranger at the fort, which is administered by Arlington County. "It’s a popular spot with bird watchers."

<b>FORT MARCY HAS</b> been well preserved over the years, and modern visitors can still see the remains of parapets, bombproof, gun platforms, gorge, well and rifle pits. Another popular spot for fort enthusiasts is Fort DuRussy, tucked into a picturesque area of Rock Creek Park. One of the most popular modern-day sites in the defenses of Washington is Fort Stevens, where President Lincoln came under direct enemy fire from forces under the command Gen. Jubal Early. A portion of the parapet and one magazine were restored by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s, and visitors to Fort Stevens can also see the nearby National Cemetery on Georgia Avenue.

"At some point, Lincoln mounted the parapet, swept by Confederate sharpshooter’s fire," wrote Owen in his description of the 1864 Battle of Fort Stevens. "Only when a surgeon was cut down nearby could the president be induced to retire from the exposed perch."

Those with an interest in heavy metal will not want to miss Fort Foote, where modern-day visitors can see two 15-inch Rodman guns, each of which weighs 20 tons, capable of firing 500-pound cannonballs three miles down the Potomac River. Constructed between 1863 and 1865, Fort Foote was the only permanent fortification for the defense of Washington, continuing its service until 1878. But not everyone was a fan. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Wells wrote in one passage of his wartime diary that the position was strong but the endeavor was a colossal waste of money.

"In going over the works a melancholy feeling came over me," Wells wrote, "that there should have been so much waste, for the fort is not wanted, and it will never fire a hostile gun."

His prediction was correct, and the giant Rodman guns were never fired during a hostile action.