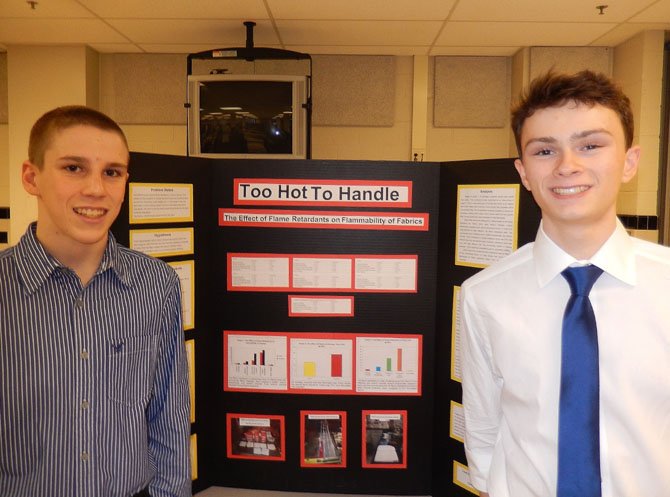

(From left) Phillip Sullivan and Liam Murphy researched flame retardants. Photo by Bonnie Hobbs.

Madison High’s Feb. 5 science fair brought out the curiosity and creativity in the students participating in it. Below, some of them explain their projects:

James Stephens

A junior, James Stephens investigated projectile motion in real life. He said that, given an upward force, a volleyball won’t just go straight up, but will curve outward and then upward.

"I wanted to prove projectile motion works," he said. "So I took measured values from my experiment and compared them to theoretical values – without any spin that would affect the curve. And I proved that projectile motion does happen in real life."

Stephens used a volleyball, plus tennis and lacrosse balls, and took a video of himself tossing each one. Then he analyzed their heights and distances. "The lacrosse ball was much closer to the actual idea of projectile motion because it was smaller and, therefore, had less air resistance."

Christina Tran, Quynh Nguyen Juniors Christina Tran and Quynh Nguyen teamed up to consider the role distance plays on falling dominoes. They decided to prove scientist Robert Banks’s universal theory about falling objects.

"We wanted to see, if we changed the distance between dominoes, would we be able to prove a theory for falling dominoes?" said Tran.

"We thought that the farther apart the dominoes were from each other, the longer it would take them to fall down," said Nguyen. "But the opposite was true. We made a pendulum of waxed floss and a marble on a Lego structure for a constant force on the first domino in a line, and all the dominoes fell down.

But, added Tran, "Our experiment was inconclusive because our velocities didn’t match the scientist’s velocities."

Sydney Goddard

Senior Sydney Goddard investigated what composts the fastest. "My neighbors have compost in their backyard and I wondered how well it worked," she said. "So I made my own compost and tested paper bowls, plus plant-based cups and forks. My hypothesis was that the paper-based bowls would compost fastest because paper breaks down pretty quickly."

Goddard put the bowls in a bin filled with a compost mixture of food and leaves and placed the bin in a closet. For six weeks, she measured the bowls’ mass weekly. "The bowls broke down first, halfway through the experiment," she said. "The cups and forks didn’t break down, at all. So people probably shouldn’t put them out to compost, at least in the short term."

Kyle Karp, Grace Rogers

Juniors Grace Rogers and Kyle Karp tested the electrolyte levels in common beverages to see how efficient they were in replenishing electrolytes in people. They tested orange, apple and lime juices, Gatorade and Powerade. They made an electrode and created a circuit to test the electric conductivity in each beverage.

"Our electrode was a straw held by two wires attached to a battery and a multimeter," said Karp.

"We dipped the straw in each beverage in a cup and took readings after one minute," added Rogers.

"We concluded that the juices, as we’d hypothesized, contained the most electrolytes, compared to Gatorade and Powerade," said Karp. "Lime juice had the most because we used 100-percent lime juice, but the other juices had sugar and water added."

Phillip Sullivan, Liam Murphy

Sophomores Phillip Sullivan and Liam Murphy considered the effect of flame retardants on a fabric’s flammability. "We wanted to find safe alternatives to commercial flame retardants because the ones currently used on children’s clothing are carcinogenic," explained Murphy.

"We cut squares of cotton and polyester and treated each with household chemicals," said Sullivan. "Then we burned them to see which burned quickly. We tested potassium alum, sodium chloride and sodium bicarbonate against a commercial flame retardant and non-treated fabrics."

They discovered, said Murphy, that "potassium alum – a food preservative you can buy in bulk in supermarkets – was almost as effective as a commercial fire retardant and could be used as a safe alternative."