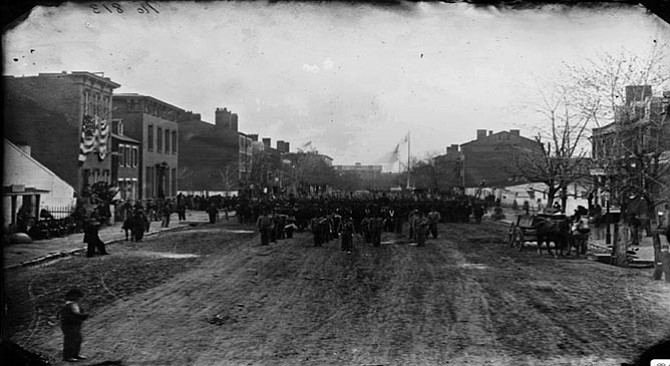

Union Troops stand on an unpaved street in D.C. before Gov. Alexander "Boss" Shepherd’s work was completed. Image contributed

North Arlington resident John Richardson, 78, the former president of the Arlington Historical Society, has written a new book — the biography of Gov. Alexander "Boss" Shepherd (1835-1902), "Alexander Robey Shepherd: The Man Who Built the Nation's Capital."

"Shepherd put the flesh on the bones of the (Pierre Charles) L'Enfant plans for the District, which were only lines on a map as late as 1870. He level-graded the streets, paved the streets, put in the sewers, planted thousands of trees, and put up the gaslights. Some of this had been done but not in any systematic way," said the former CIA officer for 25 years.

Before the work, the District was a pretty barren, muddy and torn up place, he said. "It was a shabby, beat up place after the Civil War," said Richardson. "Union troops, both wounded and active duty, were billeted throughout the District in hospitals and barracks. And virtually all of the trees had been cut down."

Richardson, who was on the Board of the Arlington Committee of 100 and lives in the Terra-Leeway Heights neighborhood, started researching the book in 1985. He devoted more time to writing it when he retired from the CIA in 2005; he finished it in 2015.

As the "czar" of the Board of Public Works, and the president of the premiere plumbing and gas fitting company in the District, Shepherd was responsible for engineering the legislative change of the district to a territorial government status in 1871. It only lasted for three years — until 1874. During that time, he consolidated the three self-government portions of the District — Washington City, Washington County, and Georgetown — to get the 10-mile square of D.C. under one legislative umbrella. As a result, they were able to issue bonds for infrastructure development.

"He built the nation's Capital. He didn't build the buildings. He built everything under the buildings. Before the Civil War, it hadn't needed a true national Capital. After the war, it did. Shepherd's work made it possible to create a true national Capital in Washington, D.C.," he said.

He added: "He implemented the L'Enfant plan. The only deviation was filling in and paving over the Washington Canal, which was an open sewer."

Richardson said that Shepherd achieved in three years what it took Baron Georges-Eugene Haussman 20 years to accomplish in rebuilding Paris. "He was a one-man gang. You couldn't stop Shepherd. What he did, in essence, was he tore up downtown Washington, and once he had it all torn up, then no one was going to see it go back to mud and dirt streets again," he said. "He created a huge uproar. Washington was just topsy turvy, hills and valleys. So he brought some rationality to the street grading process."

During his reign, Shepherd was investigated two times by Congress, but Richardson said in his research he never found any evidence of personal corruption by Shepherd. "He was way over-leveraged as a home builder and had heavy loans and personal loans; there was a financial crash in 1873; he was very exposed, and that brought him down," said Richardson.

In 1874, Shepherd was fired from the Board of Public Works; the whole government was fired when Congress canceled the territorial government and re-instituted the original form of government, which was the Commissioner System of government with three commissioners. "The District was in chaos in 1874; it was broke, and that's why Congress canceled the territorial government," he said.

"Nobody was neutral about Shepherd; he had adoring fans in the business community and many in Congress," said Richardson. "He had violent critics who hated his methods and he was accused of everything under the sun, but it was never proved."

He added: "People around him got rich; he stands guilty of practicing crony capitalism and a lot of his colleagues made money from contracts and a lot of them were unqualified."

By 1869, Shepherd, a Lincoln Republican, was the fourth wealthiest man in Washington but he declared bankruptcy in 1876. To try to get his fortune back, he moved to Mexico between 1874-1880 to seize on the silver mining business. He raised some capital and bought silver mines in a remote town of western Mexico called Copper Canyon, an isolated steep valley where all of the minerals were located, and lived there for the rest of his life.

"He pulled the whole family up and took them to the end of the earth; he hoped to come back after five years with his fortune restored, but he never again lived in Washington. He came back twice, and he died in Mexico in 1902 of appendicitis," he said.

"He made money, sure, but it wasn't consistent and there were bad years. There was another recession in 1893; the U.S. economy collapsed and the market for silver dried up and he was at the mercy of a number of forces beyond his control," said Richardson.

Shepherd came back to D.C., once in 1887, and Washington threw a huge parade and massive tribute to him. "People began to appreciate what he had done to build the physical city; he clearly came down on the side of beauty," he said. "He did something very important for the nation's capital." He also headed up a Yellow Fever Commission that brought relief to communities along the Mississippi River that had been ravaged by yellow fever.

Because he was a public figure, there was extensive newspaper coverage of his work. But Richardson said the most difficult part of his research was getting inside Shepherd's head. "There are very few letters, diaries that recount other than his experiences. There's very little that show his thought processes; but getting inside of Shepherd's head was the hardest thing," he said.

With a foreword by former mayor of Washington, D.C., Tony Williams (1999-2007), "Alexander Robey Shepherd: The Man Who Built the Nation's Capital" is available on Amazon in hardback ($59.95), paperback ($29.95) and kindle ($14.39). It is published by Ohio University Press. For more details, visit www.alexandershepherd.net.