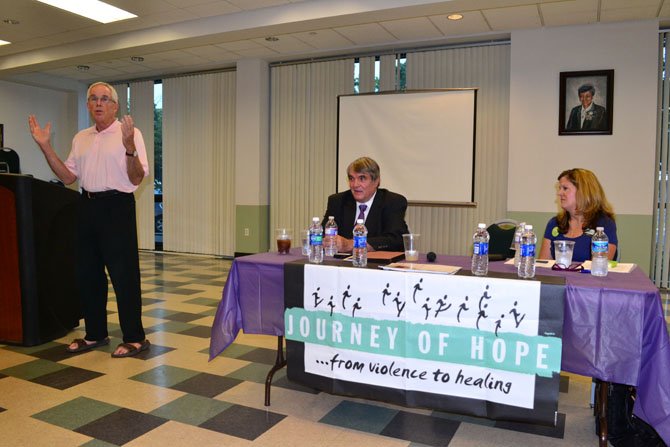

Steve Northrup, left, executive director of Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, Bill Pelke, center, co-founder of Journey of Hope, and Terri Steinberg, mother of a death row inmate.

The Journey of Hope and Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty hosted an event on Friday, June 29 in recognition of the 40th anniversary of Furman v. Georgia, a Supreme Court case that abolished capital punishment in every U.S. state. The decision was overturned by Gregg v. Georgia four years later.

“The Journey of Hope … From Violence to Healing” was founded in 1993 by five family members of murder victims. The organization promotes nonviolence, forgiveness, and an end to the death penalty.

Bill Pelke, co-founder of The Journey of Hope, began the journey after his grandmother, 78-year-old Ruth Pelke, a Bible teacher, was murdered by four teenage girls pretending to want Bible lessons in order to rob the woman.

Three of the four girls entered the home, where one hit Ruth Pelke over the head with a vase, and another, 15-year-old Paula Cooper, pulled out a knife and began to repeatedly stab the woman, while the third girl ransacked the house for money. Cooper handed off the knife to help the girl find any cash that could be stowed away. The three girls left Ruth Pelke with 33 stab wounds from a 12-inch butcher knife, and the keys to her car and $10 in their hands.

All four girls were tried as adults in the State of Indiana. The fourth girl, who had devised the plan to steal money from Ruth Pelke to play video games at a local arcade, lived across from the woman. Although she did not go with the others for fear of being recognized, the girl was sentenced to 25 years in prison.

The second conviction was for the teenage girl who had struck Ruth Pelke with a vase, sentencing her to 35 years. The two remaining girls faced either 60 years in prison, or the death penalty. Due to what the jury felt was Cooper’s ability to overpower and manipulate, the girl received 60 years in prison, while Cooper became the youngest female ever in the state to be sentenced to death.

Pelke recalled thinking it would have been unjust to have any other outcome. It was at that time, as he watched Cooper’s grandfather cry out in the court room, “They’re going to kill my baby,” that Pelke explained he began asking God for the love and compassion that he knew his own grandmother would have had for Paula Cooper and her family.

Pelke and Cooper began exchanging letters and, although state law prevented the perpetrator of a violent crime to visit with the victim’s family, Pelke continued to speak about his compassion and forgiveness for the girl.

By 1989, over 2 million people had signed a petition to get Cooper off of death row, leading to what Pelke described as embarrassment for state officials in Indiana, as the fact became known around the world that someone the age of 10 could potentially receive the death penalty there.

It was that same year that, not only did Indiana raise the minimum age for the death penalty to 16 years old, but that in a 5-0 vote in the automatic appeals before the Indiana Supreme Court, Cooper was taken off of death row and sentenced to 60 years in prison. Pelke said, “The first words to come out of my mouth were ‘Praise the Lord.’”

Currently 11 people wait on Virginia’s death row, only two of which have been convicted within the past four years. Earl Washington was pardoned in 2000 after serving 16 years in prison for rape and murder charges. Washington was the first person on Virginia’s death row to be exonerated; if released, Justin Wolfe will be the second. Wolfe was sentenced to the death penalty on Aug. 28, 2002. The sentencing took place after Owen Barber, a marijuana dealer, confessed to killing Danny Petrole, a high-grade marijuana, or “chronic,” supplier.

On the night of the murder, cell phone records showed that Wolfe, who admitted to dealing chronic, had called Barber several times. Terri Steinberg, Wolfe’s mother, recalled being proud of her son when he knew the prosecution was trying to involve him in the murder, and therefore turned himself in to clear his name.

After his confession, Barber accepted a plea bargain from Fairfax County prosecutors to ensure he would not receive the death penalty for his crime. Barber testified that Justin Wolfe hired him to kill Petrole, leading the prosecution to sentence Barber to 38 years in prison and 15 years of probation on his release.

In 2007, Barber admitted by sworn affidavit that he had lied to the jury to avoid the death penalty, confessing that Wolfe actually did not have any involvement with the murder of Danny Petrole.

Denied several rounds of appeals or the opportunity for a new trial, Wolfe, 20 years old when convicted, just celebrated his 31st birthday this past March, still on death row.

Steinberg approached the front of the crowd Friday evening at St. Charles Borromeo Catholic Church in Arlington, thanking them for coming out to listen. In reference to the death penalty, Steinberg said, “It is an ugly subject … but if it is something we don’t want to talk about, maybe it is something we shouldn’t have.”

Responding to a question about the necessity of capital punishment for a convicted murderer such as a John Allen Muhammad, one of two men charged for the series of shootings throughout Maryland, D.C., and Virginia, Steinberg spoke about the characteristics of the men she had seen or heard about on death row.

Before Muhammad was executed in 2009, Steinberg explained that he and her son had gotten to know each other. One day, she received a card in the mail from Muhammad, thanking her for the work she was doing fighting against the death penalty, as well as for raising such a caring young man, he wrote, “… that Justin brings quite a bright spot into this dark place that we call death row.”

She also recalled the day Wolfe first got to his cell. He had received the one issued pillow and blanket on arrival, and was told that all other items would have to be purchased from the commissary. When he entered the cell, he found a brown paper bag filled with soap, magazines, and other items that the men on death row had gathered for him. Steinberg said these were not people that should be put to death, “What I see,” she said, “are compassionate people.”

Steinberg expressed the hardships that her family had suffered over the past 11 years; the pain that followed as she watched two of her children struggling to concentrate through high school while their older brother waited on death row, or finding letters to Santa Claus from her youngest daughter, asking that he bring her brother home.

She continued, “The death penalty does not bring the healing that victims’ families need when they suffer such a loss. It only creates more victims in the families of the guilty, or in our case, the not so guilty.”

Both Steinberg and Pelke urged that forgiveness, love, and compassion were all necessities for moving forward, and realizing that the death penalty only stirred up hatred and anger from everyone around it. Steinberg expressed the needed healing between families involved in any violent crime through a quote by Sister Helen Prejean, an activist for the abolition of the death penalty: “It’s just like the outstretched arms of Jesus on the cross. On one hand, you have the families of the victim, and in the other, you have the families of the accused. And the only way for healing to begin is to bring it to the heart of Jesus. That is where the comfort comes.”