Tracing genealogies is not only impossibly frustrating for many African-American families, but many of the results they find are predictable and grim. But for two genealogists who hosted events at Alexandria’s Black History Museum, that idea obscures the powerful histories and proud legacies of many families.

“Many African American families have dark pasts,” said Char McCargo Bah, a professional genealogist and Alexandria historian. “Slavery, Jim Crow, the KKK … and these families say they would rather look forward to the future, that they don’t want to talk about their past. People think their families have a lot of dark sides, but they don’t know about the successes.”

Cultural historian Michael Twitty hosted a half-day class Jan. 31 on helping families trace their roots back to Africa. Bah’s lecture a week later, on Feb. 7, focused on filling in the history of local families between their ancestors being brought to America and some of the oldest records families have.

“Most African American families face a brick wall: the 1870 census, and that’s it,” said Twitty. “That’s the oldest documented ancestor most African American families [can trace to], but they have been here much longer than most white families. Many can trace their roots further back, but don’t have all of the details.”

Twitty said that African-American families have to approach geneology different from many Caucasians. While very strict documentation is at the core of most genealogical research programs, Twitty said this is impossible for many African-American families. The pieces are there, but they can’t be connected into a historical narrative. For Twitty, that narrative is key. It’s not enough to know when someone was born and when they died. The details of the life in between those dates are what makes the genealogy worthwhile.

Bah went into the detail of some local family histories. Bah had helped one local woman, Gale Brooks Ogden, discover two of her ancestors, Paul and Eliza Reddick, who were married in 1869 in Alfred Street Baptist Church. Ogden was shocked, she’d been married in the same church as her ancestors and never knew. Bah says these long-standing family traditions are fairly common, even when those practicing them don’t remember their origin. Like Twitty, Bah noted that strange family names or traditions can be major clues when uncovering a family genealogy.

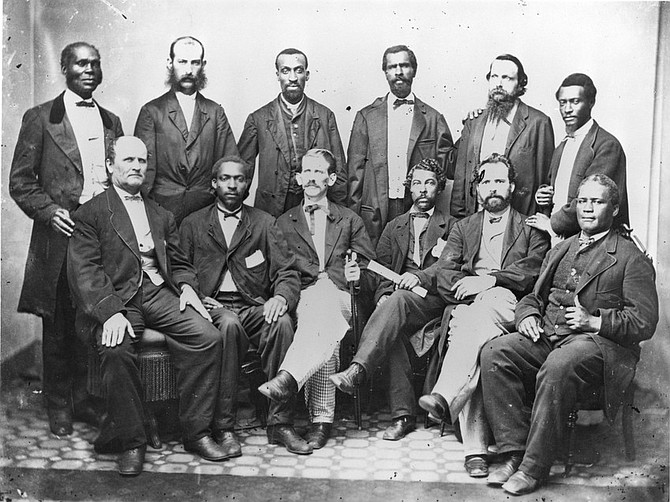

Many of the families Bah helped piece together their family histories were interwoven, either through family or both participating in the same historic events. Bah told the story of several African Americans families all tied to a trial that never happened. Several prominent African-American Alexandrians, with current day descendants still living locally, were selected to serve on the first integrated trial jury in Virginia history for the trial of Jefferson Davis on the charge of treason.

Many of the people she helps discover they have startling relations within their community.

“Many African americans that came here prior to the civil war were related,” said Bah, recounting the story of two best friends that grew up together in Alexandria and had no idea that they were cousins.

“People run around talking about ‘brother’ and ‘sister’ but you don’t realize how true that actually is,” said Twitty. “None of us know these stories as well as we think.”

Twitty’s class helped African-Americans piece together the stories of their ancestor’s lives, often using slave records to build a map of where these families have travelled. Several people in the room had already gotten the results of a DNA test but weren’t exactly sure what the results meant. Several women said they had the test and the results came back as originating from Cameroon/Congo. Twitty briefly went into some of the history of the Cameroon, back to 2000 years ago when many tribes migrated into eastern and southern Africa.

“It’s amazing to know that you’re a part of that migration, that history,” said Twitty.

DNA testing can be a tricky subject for genealogists. Bah confessed that she was originally against DNA when it started being implemented into genealogical studies.

“Where are all of the other juicy pieces that make these stories worthwhile?” Bah asked, but she says her opinions have changed over the years, and she now considers DNA a piece of the larger puzzle. In particular, she acknowledged its importance in finding a family’s origins in Africa. She was still wary of it as a substitute for genealogy.

“It’s an easy way for some people to say they’ve found their story, but you’re missing so much,” said Bah. “You don’t know who they were. You see the beginning and the end, but you miss everything in-between.”

For Twitty, knowing where in Africa the family comes from can also help identify when and where their family was brought over into America. Twitty had his own journey to trace his ancestors’ steps, which included a stop in Liverpool and London to see the docks where slaves were sold and transported.

“People don’t realize these cities are built on the slave trade,” said Twitty, citing Liverpool specifically. “They have no clue, in Liverpool, about their history. They just want to talk about the Beatles.”

Twitty’s journey took him from rural sections of Africa to a “reveal” ceremony on a North Carolina plantation not far from where his family once tilled the land. Reveals are ceremonies where a DNA test came back and traces family heritage. Twitty chose the plantation in North Carolina as part of a campaign to “take back the land taken from us.” But Twitty warned that these reveals can be bewildering.

“Parts of genealogy can be uncomfortable,” said Twitty. According to Twitty, one-third of all African Americans report at least one white ancestor. “People’s family narratives sometimes don’t fit the historical narratives. DNA sometimes washes a story out.”

Twitty says he’s encountered this with many Caucasian families he’s talked to when approached with the fact that they have African American relatives.

“They’d be very sensitive about it,” said Twitty. “They’d say things like ‘well let me check the charts’ and I just have to respond ‘listen, you’re not going to find it on the charts …’”

In Twitty’s class, Louis Diggs-Davis described a situation where she went to a family funeral and everyone there was white. She walked out initially because she thought she was at the wrong funeral. Twitty said this happens more often than people might expect, but told the class to confront the fact that they probably have white ancestry, and that it’s not something to be ashamed of.

“Discover another history you’re a part up,” Twitty said, and described roaming Central Asia or living in the Roman Empire. “That’s your history too. African Americans are told we can’t be complicated, we can’t have competing identities.”

Bah also commented that the genealogy process can be frustrating, especially when she following a life story that presents conflicting information. For instance, in one investigation, Bah found that the census was inconsistent with one man’s job from one year to another. She experienced this in her own family investigation and said it emphasized an important lesson in genealogy: for one reason or another, people lie, and that sometimes people’s lies wind up as historical record.

Bah’s had an uncle who traveled to West Virginia to work in the mines with his cousin. When Bah’s uncle arrived, he found a bunch of men gathered around his cousin’s body, drinking and laughing. He killed them, and Bah had assumed afterwards that he was killed by the local town. It wasn’t until Bah was doing more research into her family history that she discovered that her uncle actually escaped, became a buffalo soldier, and ended up getting married and retiring to West Point.

For both Bah and Twitty, the key lesson was giving historical context and understanding into what the lives of Alexandria’s African-American ancestors were like. For Bah, who helped locate and save Alexandria’s Freedmen’s Cemetery, said the only clues to its location were two elderly Alexandrians who still remembered they had family there.

“The lesson is about giving context with documentation,” said Twitty. “History will never be completely known. There’s always going to be big holes in the story. But holidays, cuisine, unusual names; they’re all vital information that can provide a clue to the family origin.”