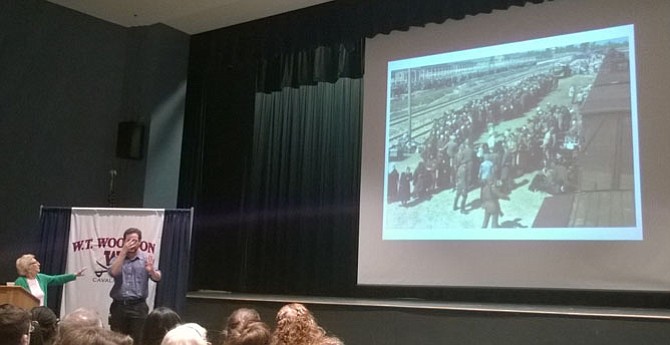

Fairfax County resident Irene Weiss, left, points to an enlarged photograph of Hungarian Jews while they were selected and processed in 1944 by Schutzstaffel guards as they stepped off a train at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in Nazi-occupied Poland. At the time, Weiss was the young woman with a kerchief — shown at the bottom of the picture, second from the left. Her mother gave her the scarf to cover the teen’s shaved head. It saved her life because it made Weiss appear old enough to join the ranks of forced laborers. People too frail to work plus women and their children are shown at the top of the page, from left to right, walking toward the gas chamber. Weiss was just separated from her younger sister and watched the child disappear into the crowd. “The drama of the separation still lingers with me today,” she said April 11 to 10th-grade students at W.T. Woodson High School in Fairfax. Photo by Marti Moore/The Connection

World War II is the focus of 10th-graders across the board in history and English classes at W.T. Woodson High School in Fairfax.

Students were transfixed Monday by a little lady with a big story to tell about her horrifying experience as a 13-year-old girl in the largest concentration and extermination camp in Nazi-occupied Poland: Auschwitz.

Holocaust survivor Irene Fogel Weiss, 85, witnessed the worst of all war crimes — genocide — and told Woodson teens about the inhumane treatment of European Jews under Nazi rule as she saw it happen for more than a year before she and other survivors were liberated by Soviet troops Jan. 27, 1945.

Her testimony is part of an enrichment program for nearly 500 students as they read in English class the Holocaust memoir “Night,” penned by another Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor — Elie Wiesel — who received the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1986 for his humanitarian efforts as chairman of the President’s Commission on the Holocaust during the Jimmy Carter administration.

“Too often words in our textbooks can become mere letters on the page,” said English department chair Ryan Brown in his opening remarks on April 11.

“Today we have a direct connection with history,” Brown told his audience before they watched Weiss’ presentation “Surviving the Holocaust.”

ALL EYES were glued to the soft-spoken dignified woman as she described her youth as one of six kids in a small farm town in Czechoslovakia, where her father ran a lumber business.

Although her community knew at the time that trouble was brewing in Germany, they didn’t think the Nazi grasp would reach all the way into their own back yard and seize control of their lives.

Then their country became occupied by Hungary in 1939. “We sat there in our little town in Hungary minding our own business.”

Hungary allied with Nazi-controlled Germany in 1940. The world of Meyer and Leah Fogel, and their six children between the ages of 6 and 17 years — Moshe, Edit, Reuven, Gershon, Irene and Serena — changed for the worse.

The human indignities started out small, with vicious propaganda as Jews were separated from society.

The sub-human conditions ended with unspeakable horror Weiss couldn’t discuss for at least 25 years after she was freed from slave labor, sorting through mountainous piles of personal property — such as eyeglasses — confiscated by Schutzstaffel guards before marching their victims to the killing machine known as Gas Chamber No. 4.

“Children were condemned to death in the world I came from,” she said, “but what was their crime?” Weiss simply asked. There was no court, no jury, no process, she recalls vividly.

Her rapt audience saw old photographs taken by SS prison guards and now in possession of the U.S. National Archives.

The images show Weiss’ separation from her parents and siblings as they were ordered off a freight train by Nazi soldiers in Auschwitz-Birkenau, following a three-day journey from Hungary to Poland in boxcar filled with 80 people and no windows.

A narrow strip near the top corner of the car provided air and light. A bucket in the middle of their small space served as the only latrine.

Surely their rank conditions couldn’t get any worse, Weiss and everyone else thought initially. The situation quickly grew abysmal at Auschwitz — which claimed the lives of more than a million men, women and children.

This killing machine consumed lives at the rate of 6,000 innocent people a day — an incomprehensible number Weiss has spent the last 70 years trying to process and may never reconcile.

Audience members stood in awe before Weiss and asked questions on several topics including mercy and forgiveness. With no bitterness, gall or vitriol in her voice, Weiss replied in her matter-of-fact manner:

“No,” the SS authorities showed no mercy whatsoever to Weiss and fellow prisoners. “They were terrifying.”

“No,” she cannot forgive Nazi soldiers who mistreated Weiss and her family — including former SS guard Oskar Gröning, against whom she testified last summer in Germany during the trial for his role as bookkeeper at Auschwitz.

Although Gröning is an elderly man of 94 years, the mere sight of him made Weiss tremble as she did when she was 13 and he wore the SS uniform.

“The magnitude of the crime … is so appalling and so painful, how could you forgive someone who participated,” she asked in response.

Germany has no capital punishment, Weiss says, and Gröning was sentenced to just 4 years in prison for his crimes as an accessory to the murder of 300,000 people. She believes he will die waiting for an appeal.

She told students “the fact I experienced something so terrible” makes it her responsibility to share her experience with everyone willing to hear. Woodson faculty were smart to record Weiss’s living history testimony last year on film and released this haunting documentary in January through the Fairfax County Public Schools television network.

THE VIDEO helped mark the annual International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the 71st anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz prisoners by Soviet soldiers.

“Surviving the Holocaust” can be seen online through the Fairfax County Public Schools television network at http://www.fcps.edu/it/fairfaxnetwork/holocaust/video_segments.html in 15 segments that offer viewers a complete discussion guide.

Part of Weiss’ account also can be read at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum at www.ushmm.org.