The City of Alexandria. The County of Arlington. The Town of Potomac.

Once, between the County of Arlington and the City of Alexandria, there was another town. Potomac, incorporated in 1908, was a hub of federal government workers residing in the area west of today’s Route 1. According to the statement of significance in the National Register of Historic Places, the story of Potomac illustrates the power of civic reform movements at the end of the 19th and early 20th century, and serves as an illustration of trends in government. Then it disappeared.

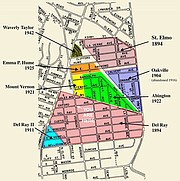

The town was annexed by Alexandria and eventually swallowed up into what is now Del Ray, but glimpses of the town’s influence are still visible. A fire station in Del Ray still bears the name “Potomac Fire Department.” The Town of Potomac was added to the the National Register of Historic Places in 1992. Interest in the history of this forgotten town has seen a revival as the Del Ray Citizens Association begins a push for greater architectural protections. Local historians have begun to reexamine the history, and legacy, of Potomac.

Much of the town was built on top of the St. Asaph’s Race Track and Gambling House, a site so popular a special spur of the railroad was built to bring patrons from D.C. The gambling operation employed 37 people, reported to be more than every house standing in Del Ray. Records say the gambling attracted violent people who attacked farmers and school children traveling through the area until in the 1890s the “Good Citizens League” was founded to put an end to the nuisance. One of the leading crusaders against the gambling operation was Joseph Supplee, who moved to Del Ray in 1895 and later became the first mayor of the Town of Potomac. The track eventually closed in 1904.

But by the early 1900s, residents of what was then called Alexandria County outside of the City of Alexandria were facing bigger issues than moral degradation. In 1900, local residents did not yet have access to electricity, water, or Alexandria City’s state of the art combined sewer system. On top of the former notorious racetrack, two developers from Ohio came together to incorporate a town to be able to better provide municipal services to the growing number of residents. The town’s incorporation was approved by the state legislature in 1908.

One third of the town worked as clerks in the federal government, another third worked in railroad-related jobs connected to the newly opened Potomac Yards railway yard. The last third provided local services, like grocers and bankers.

Much of the local culture was influenced by the same late 19th century crusade against “loose morals” that had formed the foundation of the town. It was a town that prided itself on a strict code, with slaughterhouses and drinking saloons expressly forbidden.

But this code went even further than banning libations. The town charter restricted ownership of property to “persons of the Caucasian Race” and advertisements for the town in the 1924 City Directory proudly claimed that it was the only municipality in the United States that did not have residents “of African Descent.” Until the riots in the 1960s, the town reportedly had a very active branch of the KKK.

As the Town of Potomac began to prosper, there were repeated efforts by the City of Alexandria to annex it. According to Dan Lee, research historian for the Office of Historic Alexandria, the town was bringing in considerable tax revenue. By 1928, the population had swelled to 2,355 residents. But local citizens resisted these efforts vigorously. One reason cited in the National Register of Historic Places was local residents’ indignation at the 57 bars that existed in the City of Alexandria. Annexation efforts were rebuffed in 1915, but eventually succeeded in 1929 when the City of Alexandria acquired the Town of Potomac and the Potomac Yards railway to the east.

Following its incorporation into Alexandria, the Town of Potomac morphed into the area known now as Del Ray. Melissa Butler, a historic researcher, was hired by the Del Ray Citizens Association to examine the history of the town after its annexation into Alexandria.

“Even though officially incorporated into Alexandria by 1930, there was still a strong sense of being something separate,” said Butler.

When the town was added to the National Register of Historic Places, a study was done to find all the buildings that qualified as historic properties. But that was 25 years ago, and Butler’s mission now is to find buildings that have since become eligible for listing in the National Register. These are the buildings constructed between 1941 and 1967, after the annexation, but when the town was still very independent. The main influence during that period, according to Butler, was the influx of workers related to supporting the Second World War. With things like the opening of the Torpedo Factory, new housing areas were required for laborers in the City of Alexandria. As a result, many of them were housed in brick duplexes very representative of mid-20th century styles and help tell the story of Alexandria during wartime.

“A lot of those duplexes are eligible [for listing],” said Butler. “Del Ray is known for its late Victorian, early 20th century styles. A lot of bungalows that people might consider aesthetically pleasing rather than brick duplexes, but this is no less important to historic register.”

In the years after the post-war era Butler is studying, Lee says efforts were undertaken by the City of Alexandria to revitalize Del Ray. Businesses were declining along Mount Vernon Avenue. In the 1970s, a $2 million program was implemented to provide loans and assistance to local businesses, with another $2.5 million allocated to undergrounding the utilities and modernizing the area.

Without a Board of Architectural Review, Butler says the area has faced major architectural changes inside an area that is still officially a historic district. Butler says the Citizen’s Association has expressed an interest in having a Board of Architectural Review formed, and having an updated idea of what are the historic properties within that district will be useful in that regard.

“There’s a misconception that having a historic district automatically protects things,” said Butler. “People might not think of historic districts needing to be updated, but it’s always good to consider reevaluating what’s in a district and what context it exists in. History is not stagnant.”