This is the third in an intermittent series to help citizens visualize relevant data, relationships, and trends in the city’s geographic context.

In the coming year, city government staff and the City Council will consider various zoning and affordable housing policies and practices, not least in connection with Amazon HQ2. In light of that, here’s a limited sketch of the complex issue of land use.

Jane Jacobs, an urban activist and author from the 1960s onward, wrote: “The district, and indeed as many of its internal parts as possible, must serve more than one primary function; preferably more than two. These must insure the presence of people who go outdoors on different schedules and are in the place for different purposes, but who are able to use many facilities in common.” With “a sufficiently dense concentration of people,” she argued that diverse land uses promote:

Social interaction (otherwise unacquainted people from all walks of life bumping into each other in the course of “errands” and “sidewalk life” builds “casual public trust”);

Continuous economic activity (lunch crowd, dinner crowd, etc.);

Organic safety (many eyes always on the streets).

Jacobs’ work influenced much contemporary thinking about urban planning and “placemaking.” Many of Alexandria’s planning efforts reflect her emphasis on the social good of mixed land use. For example, the 2018 South Patrick Street Housing Affordability Strategy focuses on maintaining “housing diversity,” toward “maintaining the area’s economic, social, and cultural diversity.” The 2013 Housing Master Plan says: “Mixed-income communities are the optimal way of maintaining social and cultural diversity through increased opportunities for interaction rather than isolation or polarization.”

Apart from subsidizing units, a near-proximity mixture of units types can increase the diversity of affordability levels at market rates, and thus the diversity of people who can live there. In particular, condominiums are generally much more affordable than single-family homes.

Single-family detached houses — not sharing a wall, like a duplex, townhouse/row house or stacked “multifamily” condos — are the most expensive housing type.

“Preserving the exclusivity of single-family detached neighborhoods can have negative social equity implications by erecting barriers for lower-income/ wealth families,” according to recent study from the Northern Virginia Affordable Housing Alliance. “Low-income households and racial and ethnic minorities have faced de jure and de facto barriers to full participation in the housing market, with associated impacts on wealth creation [like home equity]. … At a minimum, allowing more diverse housing types in detached single family neighborhoods reduces the barrier to entry into those neighborhoods, even absent any specific intervention to provide committed affordable [contractually rent-capped] housing opportunities.”

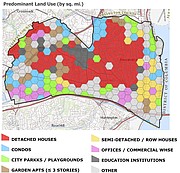

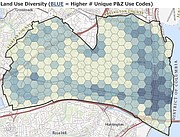

The report found that Alexandria’s zoning restricts 43 percent of residential developable area exclusively to single-family detached housing. The proportions in Arlington and Fairfax are double. In Alexandria, restrictive zoning — reflected in lower land use diversity and predominance of detached housing — concentrates in the city’s center. Areas around the city’s peripheral transit corridors allow denser single-family attached and multifamily development.

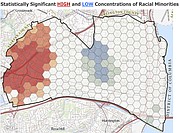

Patterns of racial segregation follow a similar pattern. Minorities (those other than non-Hispanic white) concentrate most on Alexandria’s western periphery, where condos and apartments are the predominant land uses, and least in the city’s center.

Related to mixed uses, Jacobs encouraged continuous but incremental turnover of buildings through redevelopment in order to maintain a diversity of buildings’ ages. She said: “If a city has only new buildings, the enterprises that can exist there are automatically limited to those that can support the high costs of new construction.” Whereas lower-cost “old buildings can be inexpensive incubators for new, marginal, and not-for-profit businesses,” according to Dr. Anna Marazuela Kim, writing for Thriving Cities. Jacobs called this the “economics of time,” whereby “the high building costs of one generation [become] the bargains of a following generation.”

This thinking also applies to residential buildings in a process dubbed “filtering.” The theory asserts that adding newer, more expensive units to the housing stock enables better-off households to move up. Relieved market pressures on the older stock makes the older stock more affordable to lower-income households.

Experts debate filtering’s efficacy in this regard. A 2014 nationwide study by Syracuse University’s Dr. Stuart Rosenthal indicated that rents decreased with building age, until reaching 50 years old. As a result, “for rental units, the real income of an arriving occupant at a 50-year-old home is roughly 70 percent below that of the arriving occupant of a newly built unit. For owner-occupied housing the difference is … 30 percent.” But after surpassing 50 years of age, building rents rose again. Think perhaps of costly living in historic Old Town.

Filtering also works at a slow pace. According to a 2016 research brief from U.C. Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies, housing in a high-demand market like California’s Bay Area might filter down at a rate of less than 2 percent per year. At that rate, housing built for the median income could take 50 years for household at 50 percent of the median.