Rikki George co-wrote this story

Living in Alexandria isn’t cheap and for many locals who need affordable housing, it seems to be getting more expensive by the day.

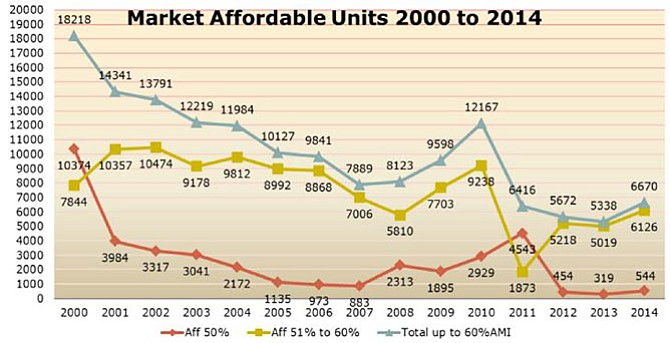

“If you look at the broad range, it’s not so good,” said Helen McIlvaine, director of the Office of Housing. “Since last January, we saw about a 2,000 unit decrease [in affordable rental apartments]. Rents have gone up in general and wages have stayed stagnant. Sometimes it does not take a great deal of movement for that to happen. It’s a trend that concerns us.”

Many of the rent increases across the city come with property owners attempted to renovate and rebrand their formerly affordable housing. Hunting Point, a pair of apartment towers near the Woodrow Wilson Bridge, came under new ownership in 2013. Since that time, it has steadily continued to increase rents and push current residents out to redevelop the property into luxury housing.

“There’s 530 units [at Hunting Point] and we might see renovations and rent increases [which] means 200 or 300 are impacted,” said McIlvaine. “It’s a big property, so whatever they do makes a big impact.”

Residents being pushed out of their homes is beginning to impact Alexandria’s nonprofits as well. Mark Moreau, intake and data quality coordinator for Bridges to Independence, says local affordable housing groups have felt the impact of increasing rents and housing loss. Bridges to Independence is a transitional program that helps Arlingtonians and Alexandrians facing homelessness find housing. In the past year, Moreau says the organization has seen an increasing number of large families in need of housing assistance.

“It isn’t getting easier,” said Moreau. “It’s very difficult to house large families, like a family of nine or the family of eight. We’ve partnered with [other organizations] for that, combining two two-bedroom units into one four-bedroom unit.”

But Bridges to Independence faces its own internal pressures. Moreau says Bridges to Independence gets 75 percent of its funding from the office of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and other government resources, which has been pushing for the non-profit to move people quickly through the program.

“There is a push to get people out of the shelters quicker and not keep people in transitional housing,” said Moreau. “If you put people in housing too quickly without support, it sets them up to fail. But HUD and others have argued that it is the model they’re pursuing. We’ve adjusted to that, but a lot of the staff are not thrilled about it. We would like to keep people in the shelter longer to help them work through issues.”

Where Bridges to Independence used to keep families for up to two years, and generally at least six months, the push has been to get that number down to four months. But Moreau says there are other issues homeless citizens are facing that can’t be fixed in four months. Moreau says some need mental health support, while others have little to no source of income. If they have criminal records, Moreau says that can make finding employment difficult. The non-profit also helps those who might have a murky immigration status, which also makes finding employment and housing a challenge.

“Some of our folks have a hard time getting approved for an apartment because they have bad credit or even no credit,” said Moreau. “It [was] initially shocking to me; people with no credit getting turned down. We’re seeing more young people in transition age youth, 18-24. Some are adult children with parents. We had a 20-year-old that was pregnant with first child. It’s harder [to find housing] with no rental history. That affects their chances of qualifying.”

As the city continues to hemorrhage market affordable housing, the committed affordable housing can’t keep up, despite a relatively “good year” in 2015. McIlvaine pointed to Jackson Crossing, a new 78-unit affordable housing complex in the Potomac Yards that opened in April, and the nearby 28-unit Lynhaven Apartments. Other committed affordable units are coming in at scattered new developments, like 45 rental set-aside units at Notch 8 and 33 units at the Parc Meridian apartments across from the new National Science Foundation building. All of these are located near current or planned metro stations, which McIlvaine said was part of the guidance from City Council.

Alexandria also has two major committed affordable housing projects emerging: the redevelopment of the Church of the Resurrection property into a 100-132 unit housing complex and the redevelopment of the Carpenter's Shelter that will include 90 affordable rental units above the current shelter. But there’s a catch. McIlvaine said construction costs could range from $5 million to $8 million, which would use all of the department’s funds, as well as general obligation bond funding, to provide support for the tax credit that would make construction possible. One project will move forward in 2017, the other is forced to wait a year to secure additional funding.

New housing can’t come soon enough for Alexandrians in need. The Alexandria Housing Development Corporation (AHDC) has 183 units of committed affordable housing in the city, all but two of which are occupied.

“There are next to no vacancies,” said Jon Frederick, executive director of AHDC.