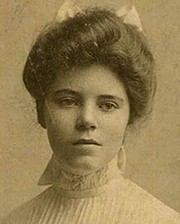

Alice Reagan, Associate Professor of History, Northern Virginia Community College, gives a talk on the Occoquan Suffrage Prisoners. Photo by Steve Hibbard.

Alice Reagan, a history professor at Northern Virginia Community College, gave a history talk on the women’s suffrage movement titled “The Occoquan Suffrage Prisoners,” at Lorton Library on International Women’s Day on Thursday, March 8. Reagan, a Lake Ridge resident who also works at Lucy Burns Museum at Lorton Prison, outlined the events that happened in our backyard nearly 100 years ago that led to women’s right to vote. The following is a condensed transcript:

In the early 19-teen years, a woman named Alice Paul was a Quaker from New Jersey who met Inez Milholland while she was in England for graduate school. Milholland was a lawyer interested in the suffrage movement. Alice also met Lucy Burns and Harriot Stanton Blatch who was the daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Alice Paul and Lucy Burns met in London after both were arrested for supporting British women trying to get the vote. They decided to come back to the U.S. and shake things up with the women’s movement. Alice Paul’s emphasis was on public displays and parades, which she picked up from Emmeline Pankhurst.

AT THAT TIME, the dominant women’s suffrage association was called NAWSA, the National American Women’s Suffrage Association. NAWSA leaders believed that if they could get enough states to approve suffrage, and that states would elect pro-suffrage Congressmen. But Alice and her friends said what’s needed was a National Amendment.

In 1912, the National Women’s Party (NWP) decided to target Woodrow Wilson and the Democrats. When Wilson arrived for his presidential inaugural, he got a nasty shock because Inez Milholland, on horseback, was leading 8,000 women suffragists in a parade.

Inez had been leading many parades and burning the candle at both ends with her work. In 1916, she went on a campaign out West and developed a bad case of tonsillitis and anemia. At the age of 30, she died from the complications.

At this point, the women’s party passed a resolution calling on Wilson to support a federal amendment in memory of Inez. In 1917, some 300 members of the women’s party visited Wilson at the White House, who was not very happy about it. Next, Alice and Harriet Blatch decided to change tactics by taking protests to a militant level and picketing the White House for the first time. On Jan. 10, some 12 women’s party members called “The Silent Sentinels” picketed the White House. They carried banners saying, “Mr. President, How Much Longer Should Women Wait for Liberty?”

On March 4, more than 1,000 women picketed the White House on the eve of Wilson’s second inaugural. Mobs began to harass Alice and her friends so Wilson decided to have women arrested for blocking the sidewalk. Lucy Burns was also charged with obstructing the sidewalk.

It is estimated that there were 2,000 women who picketed in D.C. and 500 were arrested. Of those, 168 received jail sentences but not all in Occoquan Workhouse. And 106 women were sentenced with 72 serving in Occoquan.

On July 4, 1917, some 11 additional women including Lucy Burns and Dora Lewis were arrested and served three days in D.C. jail. By mid-July, the authorities decided to get tougher with the women and took them to Occoquan to the Women’s Workhouse, which opened in 1912. At the Workhouse, the prisoners were pickpockets, drunks, shoplifters, bootleggers, and prostitutes. From July to November, 1917, some 72 women were sent to Workhouse in effort to separate them from Alice Paul and her followers.

THE FIRST SUFFRAGIST PRISONERS were sentenced on July 14 (Bastille Day), to Occoquan for 60 days when they refused to pay fines. After some negotiation, the women were pardoned after three days. They didn’t want to accept the pardon. What set off problems with the women and Wilson was the Kaiser Wilson banner.

Organized by Lucy Burns, the women kept producing banners and flags in Cameron House. So then 11 women were sent to Occoquan for 60 days after they protested during a parade on Labor Day. Pauline Adams, a radical suffragist, was arrested; she was the first woman to insist they were political prisoners. On Oct. 21, they returned women to the D.C. jail because there weren’t enough cells at Occoquan. Lucy Burns was part of the group.

Pauline Adams served a 60-day sentence. After Sept. 14, 10 additional women were sent to Occoquan.

There was a big scandal as unsavory stories about how prisoners were treated started leaking out. She testified before a D.C. Commission. There were mass arrests when Alice Paul got arrested herself for picketing. Alice was isolated at the D.C. jail and force fed. After more protests, 31 women were sentenced to Occoquan led by Lucy Burns and Dora Lewis. Burns received a 6-month sentence.

On Nov. 15, Mr. Whittaker, the Occoquan warden, decided to get tough with ladies by sending guards with clubs to terrorize the 33 women prisoners at Occoquan. The women were thrown into cells, beaten, kicked, and thrown around. They left Lucy Burns chained to her cell door overnight. Dora Lewis, a wealthy widow from Philadelphia, got her head bashed against the wall. The suffragists went on hunger strikes so the authorities force-fed Lucy Burns and Dora Lewis because they were afraid the women would die. Burns and Lewis were moved to the D.C. jail and put in the hospital.

On Nov. 23, women who were weak from their forced feedings appeared in federal District Court and collapsed in front of the judge, which shocked everyone. The judge ruled that these wealthy women should not be sent to Occoquan anymore so they were released from D.C. Jail on Dec. 27 and 28.

The women’s convictions were then tossed out by federal courts. Faced with an outcry over the suffragists’ treatment in Occoquan, Wilson announced he would support the Women’s Suffrage Amendment.

Congress passed the 19th Amendment in 1919 and it went to the states to be ratified. How did they get the amendment approved? The Western states were the first to grant suffrage. And the state of Tennessee provided the breakthrough when a young man named Harry Burn voted “yes” for the ratification after his mother sent him a note urging him to do so. The 19th Amendment was ratified on Aug. 18, 1920.