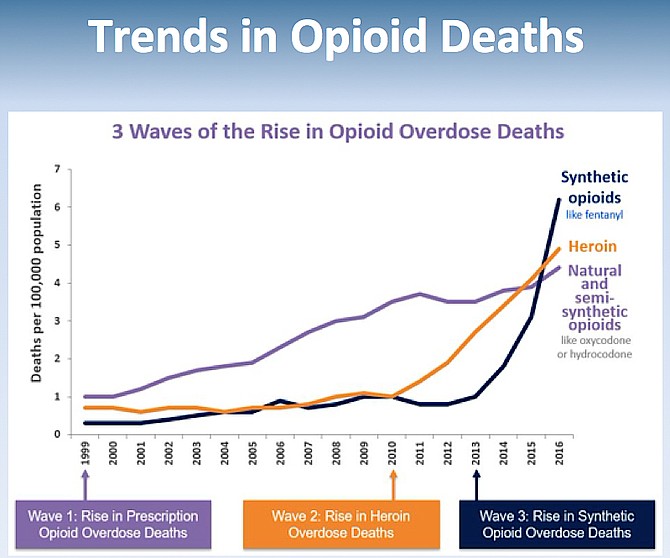

1999 saw a rise in prescription opioid overdose deaths, 2010 saw a rise in heroin overdose deaths; 2016-current sees an escalation in synthetic opioids overdose deaths. Screenshot via Drug Prevention Public Forum. Source: CDC

The opioid and drug abuse epidemic is not “there;” it's here in Northern Virginia. The abuse knows no demographic or socioeconomic boundaries. Six organizations, all stakeholders in three Fairfax County communities, Great Falls, McLean and Herndon, took on opioids and drug abuse at the primary level, education. They co-sponsored a 90-minute, four person-panel featuring state, regional, and local experts. The goal was to educate the public about the epidemic plaguing Northern Virginia, share novel ways to control it, and ultimately eradicate the problem.

"This isn't about crime-fighting; it isn't about prescribing; it isn't simply about medicine. It's about how we work together to solve problems in ways that we don't normally do," said Keynote Speaker, William Hazel, M.D. at the Public Forum – Operation Drug Prevention held Feb. 29, in Great Falls, organized by Rotary Club of Great Falls and Great Falls Citizens Association.

Hazel, an orthopedic surgeon, served two terms as the Commonwealth's Secretary of Health and Human Resources, first appointed in 2010 by Gov. Robert McDonnell (R) and then reappointed in 2014 by Gov. Terry McAuliffe (D). Currently, Hazel is the Senior Advisor for Innovation and Community Engagement at George Mason University, where his initial focus was to spearhead a multidisciplinary initiative to fight the opioid epidemic in Northern Virginia. "We need to understand; this is not simply a moral failure; it's a disease. It's not simply about opioids; it's a number of substances amongst them...We need to think a little bit about how people with substances can come back into their community and have hope and have a life. We need to think about those types of things if we're going to solve this. And we need to make new relationships," he said.

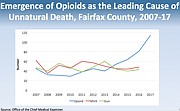

HAZEL did not mince words describing opioids and drug abuse that is running rampant in Northern Virginia. "People talk about substance use addiction as a disease of despair," said Hazel. He referenced statistics dating back to 2013 and southwestern Virginia. "We were losing more people to opioid overdoses than car accidents and gun violence...That has continued into 2019...And Fairfax County has a similar path with the emergence of fatal opioid overdoses as the leading cause of unnatural death in Fairfax County," he said, citing data from the Chief Medical Examiner, 2007-17.

According to Hazel, one of the things people in Northern Virginia have to change in their thinking is "that this happens to them, but it is actually us."

Hazel said while some may consider current drug abuse a heroin problem, it's not. "They're dying from prescription drugs; WE are dying from prescription drugs," said Hazel Trends in opioid deaths since 1999 show three waves. Wave 1- 1999: Rise in prescription opioid overdose deaths; Wave 2-2010: Rise in heroin overdose deaths; and Wave 3- 2013: Rise in synthetic opioid deaths.

According to Hazel, opioids are not a single drug but a class of drugs. The class includes natural and semi-synthetic opioids, like oxycodone and hydrocodone, and synthetic opioids like fentanyl, 80-100 times stronger than morphine, according to a DEA.gov fact sheet, and fentanyl analogs like carfentanil used to sedate elephants. It is estimated to have 10,000 times the potency of morphine, according to Suzuki J, El-Haddad S. in A review: Fentanyl and non-pharmaceutical fentanyls (2016). “Very, very potent stuff, even to come in physical contact with," Hazel said, referencing first responder exposure to the powder form. Then there were other substances like Pentazocine and Valium, as well as Cocaine, a drug of the affluent.

Using data science, Hazel displayed maps of Virginia, color-coded to indicate numbers and types of drug-related deaths. One slide showed the rate of methamphetamine overdoses, 2016-18 by locality, with high markers clustered up and down the western state line of the Commonwealth. "Anyone know what this is," Hazel asked—(the I-81 corridor.) Hazel said following a leveling off of opioid deaths in Frederick County and Winchester, they then saw increased methamphetamine and cocaine deaths as the drug(s) traveled eastward. Drug distribution networks, patterns of traffic mattered.

While certain age groups such as 18-25-year-olds were more likely to experiment with and abuse prescription and illegal opioids, no age group in Fairfax County was immune. "We all think about perhaps younger folks, but it does happen in older folks," Hazel said, calling attention to the health crisis of rising older adult drug overdoses. A lot of prescription medications out there, and that matters," Hazel said.

"We have data from surveys, which show that kids are using opioids more or misusing prescription medications, at a very high rate and young age... It's that available out there," Hazel said. He described pill parties (pharming parties) with their peer pressure. "You bring a handful of pills; you put them in the bowl. You take some, and that's your admission to the party on Friday night," he said.

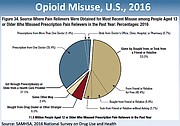

"Where are the pills coming from," asked Hazel. Over 50 percent of opioid-misuse, in the U.S. in 2016, got them from someplace else, not through a prescription, stolen or bought according to Hazel. "You know, we prescribe it, and it sits in the medicine cabinet, and someone else takes it," he said.

ACCORDING TO HAZEL, when he was Secretary, they had to put in rules about people coming in to refill prescriptions for deceased relatives; they had to have the drug. The drive to get narcotics once addicted was significant; however, addiction is a disease, like other diseases such as breast and lung cancer. Physicians know the cells are different in individual responses to treatment. "There will be some people that will respond to absence treatment and 12-step programs that work (for addiction), but others won't." Hazel showed slides of decreased metabolic activity in a healthy brain vs. a diseased brain of cocaine abuser and said, "Your brain changes... We know that when you come in and have surgery, and I give you narcotics, within 48 hours, your body begins to adapt to those, and you begin to develop tolerance...We know that somewhere along the line, some people become habituated, even addicted, even that early. And we know that when you withdraw it, it creates symptoms... "dopesickness...At some point, the craving for the substance is no longer to get high; it's to avoid feeling awful - the most miserable feeling of the world...when you talk to people who have had it, they'll do anything to avoid it." Hazel said how people committed the crime of breaking and entering to get pharmacological treatments like Suboxone to prevent that feeling. He added that as Secretary, regulations were put in place to prescribe such medications to treat people in jail, "to meet them halfway... so they would feel more comfortable with the treatment."

As for who gets addicted and why Hazel said it might be genetic, environmental, a host of other factors. "We don't know, and we also don't know today who needs how much medication and for how long. We do know whether it's in the criminal justice population, or the non-criminal justice-involved population that medically - assisted treatment gets a much, much higher rate of stay in recovery for longer periods."

In addressing Virginia's Response to taking on Opioids and Drug Abuse, Hazel discussed five areas.

The first, Harm to Addicts and Others, beginning with the addict. "Oh, you're going to give needles to addicts. Right? Well, the reason you think about that is so that you're not transmitting hepatitis and HIV and endocarditis," he said. There are now four sites in Virginia that have chosen to do that. Law enforcement and the community agreed that this would be the case. According to Hazel, incarceration became a major place for people with substance use and mental illness to reside, but that brought inherent harm-to-self dangers. Thirty days of drug absence was not thirty days of treatment; thirty days of absence reduced the tolerance to drugs by abusers. When they went back out, since abusers had burned bridges with their families, they turned to people they associated with before and got the same substance. "The first 14 days out of jail are one of the highest rates of fatal overdose. We don't think about that as well as we can probably in incarceration," he said.

According to Hazel, it was a physician's responsibility to practice "good medicine," and if the patient was substance use disorder with treatment not available, and they needed the medication, "far better for them they have a prescription medicine than go to the street."

AS FOR “OTHERS,” Hazel said that the leading cause of children coming into the foster care system was substance abuse. Eventually, the numbers overwhelmed the system. Addiction harmed others, children impacted by ACEs, Adverse Childhood Experiences.

"This may be the most important thing I mention today... We know...children exposed to certain non-physical traumas, develop physical symptoms earlier in life, children exposed to three or four and what we call Adverse Childhood Experiences- homelessness, hunger, family violence, substance use, incarcerated parents, those types of things. Great stresses in the growing body, which creates changes in the brain... And we know that those... kids who are exposed to this will develop the earlier onset of cardiovascular disease and diabetes...They don't have a chance."

The second Virginia Response centered on Prevention-getting prescriptions out of medicine cabinets, especially for first-time users. Disposal boxes such as the ones countywide accept drugs no questions asked, making it easier for community residents to dispose of unused medicines from their homes.

The third Virginia Response, Initiating and Maintaining Recovery, meant not treating in jails, especially with all the contraband issues there. "When you're an officer... you take them to booking... It is hard in most places to get people into treatment... we have to think about making that more available... The best treatment is medically assisted.

The fourth Virginia Response was to Interdict the Illegal Supply. "We have to work with our law enforcement because the bad guys are out there and they're predatory. We need to get it stopped. This flow of fentanyl that comes in can be delivered to your house from Mexico or China. It's there. International treaties are involved. The same groups do drugs, human trafficking, money laundering, huge complex webs of crime. We can't deal with that, but we have to separate the criminals, the bad guys," he said.

According to Hazel, the fifth and final Virginia Response was there had to be a Culture Change, and we had to get rid of the stigma. He said, "It ain't okay, to put stuff in your body that you shouldn't...If it hurts, it's going to be okay...Understand narcotics don't work any better than ibuprofen or Tylenol for most things. Stop demanding drugs. If someone is in recovery, comes back into the community, and they're not accepted - they can't get a job. They can't take care of themselves... their family pays for that. We need our people back and being productive. So we have to think about how we welcome people in recovery. We have to get rid of the stigma. That is the biggest front we face."